Haiti Southwest Roadtrip, January 24th, 2013 - January 27th, 2014

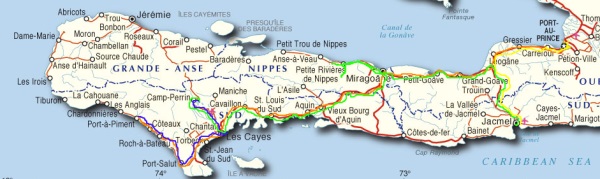

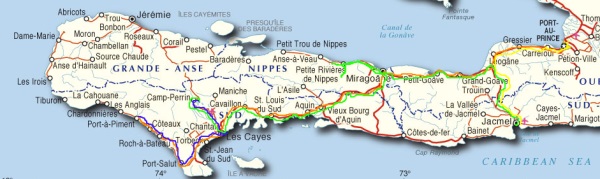

FLL -> Port au Prince -> Port-a-Piment -> Point Sable -> Les Cayes -> Camp Perrin -> Saint Luis de Sud -> Petite Riviere de Nippes -> Jacmel -> PAP -> FLL

Emily got it into her head that she wanted to go to Haiti. She was now an employee at SpiritAir and had, in the last two months, earned the right to fly anywhere on Spirit or United for only the cost of taxes - Delta would be tacked on if she stuck it out for another year - but for now, Vegas, the Caribbean, and Central America were the top choices for a weekend getaway. Aside from a 2-day stint in the resorts of Cancun, she had never been to a developing country before, so it struck me as odd that she should pick the least developed nation in the western hemisphere and one of the most perennially challenging travel destinations around. She knew it would be unwise to go alone, and that I had survived two previous visits to Hispanola, so she offered me one of a handful of companion passes. This was enough to convince me to set aside a four-day weekend and book a bus ticket to South Florida.

Emily had a friend who was working on a yacht in a Fort Lauderdale marina, just east of the airport. We slept there and got to the airport by 6AM. Our tickets were standby, but there were 90 seats open, so they went ahead and reserved a row for each of us.

A Peppery Start

The makeshift drums and banjos still sounded across the tarmac, as they had four years before. My Europcar reservation said "Arrivals Hall Pickup", but we found no sign bearing my name. The rentals hall had a dozen companies represented, but ours was "Off-Terminal" - we got vague walking directions from a taxi driver determined to sell us a $15 ride. The airport's lone ATM had been unplugged that morning; no one could say when it would be back online.

We found a bank in a small shack just outside the airport fence. The teller calculated 3400 gourdes for our $80USD, then proceeded to doll out 8500. I figured this was a symptom of my weak understanding of the Haitian currency and its mixture of gourdes and dollars, but while I was still splitting this sum, she called us back to take back the extra five grand. It might have been nice to have an extra hundred bucks on hand. I would have bought a lot more ice cream.

The enormous tent city that once bordered the airfield had vanished. When I had visited the city in 2011, remarkably little had changed since the earthquake had struck. But here, three years later, was a clear-cut sign that progress was being made. The ditch lining the road still let loose an overpowering stench of rotting sewage. Interestingly, West Africa and Haiti have the same expression for the pace of development: piti piti - small small.

There was not a single corner of our bright red Mazda 2 without some gash, crack, or contusion. The attendant carefully added each detail in turn to the vehicle condition report, until the entire diagram was shaded black. Only the roof was clear.

We expertly dodged any and all points of interest on the five-hour drive west to Port-a-Piment. Roadside markets proved a very different sort of challenge with a car. The second we stopped, we were instantly assaulted by a dozen ladies with baskets of pomelos. Emily remained in the passenger seat, unwilling to so much as crack the door for fear that a pomelo might be forced through. We found a rice vendor and got a standard box of rice, beans, veggies and chicken. Emily is a vegan, so I ate the veggies (in meat sauce) and the chicken, and left the dry diri ak pwa for her. Haitian street food typically sucked for Emily.

We never found a sim card, so rather than call a cave guide in Port-a-Piment, we just stopped at a random house and asked for one. Naturally, one of the guys standing there was more than happy to assist and jumped in the backseat. We circled the town a few times and found the guy with the keys; the cave had closed a few hours before, but they sold us tickets anyway and, in the last minutes of daylight, led us up the hill to the entrance. Marie Jean cave with its three gaping entrances and underground gardens, would have been far more impressive in the daylight. When we reached the crawl for the remaining four kilometers of passage, we found that bats were streaming out of it by the hundreds. This was the end of our tour.

We asked about cheap hotels and were led to an unsigned guesthouse with rooms for $12 a night. This was far better than the $80 rooms that are the norm in the guidebook. The guesthouse doubled as a two-screen movie theater which, when we arrived, was showing a French-dubbed version of White House Down for 10 gourdes a seat.

|

| Our bright red car in the drab streets of Port-a-Piment |

Coconuts and Quebecois

We searched the quiet streets of Port-a-Piment for breakfast but only found spaghetti. In Haiti, spaghetti is primarily a breakfast food and is always served smothered in ketchup, mayo and hotdogs. There was little chance of this dish being redeemed for the discerning vegan.

Heading off into the sunrise, we soon reached Coteaux, which was home to something called The 500 Steps. With no signage or paths going to them, they proved remarkably hard to find; we missed them by a few hundred meters and spent an hour bushwhacking up and around the top of the mountain, following the beckonings and directions of random goatherders and charcoal-makers that appeared along the way. Exhausted upon returning to the base, we were less than excited when a villager took us straight to the steps. We dutifully climbed to the top, passing signs that appeared to be drawing a parallel between the trial of the steps and the Crucifixion. One-thousand steps later, we were back at the start; here a lady informed us, very matter-of-factly, that we either had to take a stone and put it at the top of the steps, or give her money. I had no idea who this lady was, or whether she had any right to make such a claim, but when presented with these two alternatives, much like a gag reflex I snatched a twenty gourde note out of my pocket and dropped it in her hand.

There was no breakfast in Coteaux either. We saw people carrying around baguettes, but the shop marked as the boulangerie sold only nail polish and hair extensions. A large market had formed and we bought four bananas from one lady for 10 gourdes. She insisted that she had no change for our 25-gourde note and had no way of getting it from the 50 people who surrounded her - the only option available to us was to buy the remainder of her bananas for 15. This went on for some ten minutes until a local official showed up and told her to give us change; she traded our bill away in less than 20 seconds.

We continued onward to Pont Sable, which is a pretty fantastic strand of white sand with a 150-gourde admission fee. The beach was filled with a gaggle of Quebecois who were taking a day off from their nearby mission. Some were helping to haul in the day's catch when we arrived. Most visitors to Haiti, almost exclusively volunteers or NGO workers, seem to be helpful in this way - not us - we were just there to drink from a coconut and lounge on the beach.

|

| Sunrise over Coteaux |

|

| On the quest to find 500 steps |

|

| The 500 steps |

|

| Quebecois tourists hauling in the day's catch |

|

| Fishing net made of old flip flops |

|

| Small waterfall outside Port Salut |

Out of the Woodwork

Les Cayes is a very manageable city with broad streets and plenty of neat colonial buildings. Since it was now lunch time, there were several dozen street vendors on hand selling all manner of rice and beans. None offered a meatless option. I found an ice cream shop and picked up a tub of Flintstones Orange; this was not vegan-friendly either.

The road to Camp Perrin was beautifully paved and brought us quickly up into the mountainous center of the southwest peninsula. We parked in front of the town's cathedral and asked the first passer-by about the cave. Naturally, he was more than happy to take us there and hopped in the backseat. Emmanuel took us to his wife's house to park (apparently she was crazy and he was planning to leave her shortly, and it was perfectly permissible that he should take Emily's number and give her a call once she was back in the States). We hiked up the river bed; en route, a small boy latched onto our group to join the tour. As we climbed a steep hill, a man jogged up, panting; he was the official cave guide and we were supposed to have called him twenty minutes before arriving. This was an offence easily forgiven, and he took over the spot at the front of the pack for the remaining half kilometer to the main gate.

The foreign caving group that had built gates and established guide services for three caves in the southwestern peninsula had fixed the price for cave entry at 100 gourdes a person. Our guide decided he wanted at least 500 - and this was for the ‘basic' package. He eventually settled for 300, paid in advance, but he would only give us a taste, and we should probably give something to the small boy that had followed us - though he had yet to say a word.

The guide led us around the various rooms and explained how stalagmites and stalactites formed, and had us take his picture while he posed on various formations, and demonstrated how it was safe to drink out of pools of water formed by drips from the ceiling, and had everyone turn off their lights so he could sing a gospel hymn in complete darkness. He seemed ready to take us deeper into the cave, but then abruptly changed his mind and led us back to the surface. He let us out through both gates, but as we exited the second, he said goodbye, closed the door, and locked himself inside the compound; he would apparently not be returning to his village.

|

| Streets of Les Cayes |

|

| Our cave guides requested multiple pictures on formations |

Deploy the Space Blanket!

Emmanuel insisted that he accompany us to Saut Mathurine, the largest waterfall in the country. We had planned to camp at the falls and take back roads to the coast the next day, and it was not clear how our clingy guide fit into this plan, but we had only half an hour of daylight remaining and zero time to argue.

We arrived at the falls at dusk and someone materialized at the gate, claiming that he was the guide and that we had to tip him at least 150 gourdes. What we could possibly do with a guide on a 200m paved walkway was a mystery, but I dug out the cash and we raced down to the falls.

The waterfall was turned off on this particular day. It was rerouted to generate electricity for the entire dry season. I found it interesting that this had not been mentioned at the gate. I hopped across rocks to get out into the middle of the stream, closely followed by a gang of random children who had apparently latched on to us in the village. Emily followed but fell in and soaked both her shoes. I prepared to strip down and swim in the bright blue pool. The guide intervened, "Be careful - the pool is very dangerous because of strong currents - even if you know how to swim, you may be swept away" - this was the first he had said to us since the gate. I looked incredulously at the perfectly still waters. The children leapt and danced around me and the guide looked on with arms folded. I decided I didn't feel much like swimming after all.

We asked if there were any places to stay in the village. The guide pointed us to a hotel next to the waterfall. We walked into the empty lobby and shouted a request for a room over the deafening music. "$50", the DJ said, gesturing to a dark, claustrophobic hallway to our left. We said we would camp instead. "You can sleep in my house!" the guide exclaimed, "...and eat dinner here." There was no sign of a kitchen and the cheapest thing on the menu was 500 gourdes; we explained that we would eat granola. "You can eat my wife's cooking!" the guide offered once again. This had worked out perfectly.

We ordered a mototaxi for Emmanuel and gave him 100 gourdes for the ride home. He had taken the liberty of borrowing Emily's headlamp from the cup holder of our car and left without giving it back - perhaps this was why he never stopped to ask for a tip. The guide's wife set up a dining table with an immaculately white tablecloth, and laid out a meal of diri ak pwa and some sort of sauce made up of oil and beef jerky. After finishing our meal, our patron asked if we would like to watch some TV. With little else to do, we said we would, and he led us into the living room and put on a Bollywood movie called Commando. The movie was in Hindi and had no subtitles; we asked about this, but he could not understand our complaint; that's just how this movie was - the dialogue wasn't supposed to be intelligible. The children followed along with the dance numbers beside us, perfectly mimicking each move.

We made a group trip to the toilet. Our host's toilet was in some way inadequate, so we went to his father's down the road. I went first and walked around the USAid wall to the inverted clay cone where I was to squat. Our host stood in front of me and waited expectantly, holding up the light. I explained to him in broken French that this arrangement was not going to work and he needed to stand around the corner. When this failed, I walked around and got Emily to explain to him the American proclivity for privacy.

Back at the house, our host showed us to the master bedroom, which was separated by a curtain from the space where the family of five would sleep. He set a bucket next to our bed in case we needed to pee in the middle of the night. Sleep was not easy, as we had no mosquito net, and an array of biting and stinging bugs assaulted us. When layering my clothes atop my bare skin failed, I unfolded my space blanket; this process might have awoken the whole town, had it not been for the drone of ground-shaking hip hop that never relented. This kept off all but the most persistent bugs and afforded me a few hours of sleep, but I was frequently awoken by each volley of crinkling that accompanied my every move. I also woke up when one of the children made use of the bucket two feet from where we slept.

In the morning, we went down to the waterfall and swam unaccompanied. When we returned, coffee was ready and the tablecloth had been laid out once again. One of the children had taken a huge dump on the front porch; our host apologized for this. We finished our coffee and bid farewell, handing over a roll of bills for our food and lodging, which was reluctantly accepted.

The Waterfall that Nearly Was

We had listened in horror as one downpour after another fell on the tin roof of our shack over the course of the night. The route to the waterfall was a steep, rough track - enough rain, and there would be no way for our little 2WD Mazda to make it out again. We had already mentally prepared ourselves for an extended stay in Saut Mathurine village. But the jungle did an admirable job of soaking up each new round of runoff, and we made it up every slope on our first try.

The next stop on the tour was a pair of ruined forts on the western edge of St. Louis del Sud. A guide showed up to take us through the first fort and explain each room; a chain of a dozen children followed us and clambered through the windows and monkeyed over the cannons. The other fort was on an island a few hundred yards offshore and we needed a sailboat to get there. The guide gave us an initial price of 500 gourdes, and I countered with an offer of 150. I expected this to be the start of a negotiation, but he simply disappeared, never to be seen again. Unsure of what to do, we walked back to our car, and looking around one last time in the hopes that someone would show up and make a second offer, we got in and drove away. This was a real bummer given that the fort on the island was reputed to be far more impressive than the one onshore, and the ride out was supposed to be simply magical; I vowed to put more work into my haggling skills.

We drove to what we believed was the town of Petite Riviere du Nippes and inquired after a waterfall that was supposed to be a 3-hour hike away. Only one person had heard of it, and he informed us that we were in fact an hour's drive away from the Petite Riviere that we sought. We drove through Miragoane and out onto a scenic coastal road that ran through a number of fishing villages. We asked about fifteen people for directions and still missed the turn; 5km further down the dusty road to Jeremie, we questioned another man whose only reply was "lost" - he walked away shaking his head.

The cheapest way to buy water in Haiti and much of the developing world is in the form of 300ml plastic sachets. The environmental implications of these things are a bit scary, but they do provide nearly ubiquitous clean water. After being consistently dehydrated for the first two days, I decided that we would invest 50 gourdes to get a 100-pack of the sachets. We quickly realized this was way too much water and resolved to start giving them away to everyone who appeared to be in need. This proved easier than expected, as the first person we asked for directions, an aged man making charcoal on the edge of the sea, started off the conversation with "I need water". With much delight, we shoveled a pile of sachets into his waiting arms, he flashed us an exceeding grateful smile, and we continued on to find our next recipient.

A narrow, bumpy road led from the coast up into the mountains. It was not much of a challenge to the mighty Mazda, until we crested one hill where the road seemed to drop off a cliff. Even in the best of conditions, there was no way we would make it back up this slope. We parked in someone's yard and negotiated with two mototaxis to take us the rest of the way to the cascade at Saut Barril. The road ran through three different knee-deep streams and up innumerable boulder-strewn ascents; a lesser rider would surely have tumbled over and broken a hip. The tire on my bike went flat and I had to hop onto the back of Emily's for the remainder of the ride; the extra 150lbs made it that much harder to balance, and our driver's nerves, as well as our own, were stretched to their limits.

We arrived in the village of Saut Barril; we somehow got the impression that we were supposed to wait in the shade for the tire to be fixed before we continued onto the falls. A drunk staggered up to us and offered to be our guide to the waterfall and we politely declined. We toured the church and conversed with some of the locals - and by this I mean, Emily conversed with some of the locals while I stood there silently and tried to simultaneously look both amiable and intimidating. Since our encounter with Emmanuel, my title had switched from "friend" to "fiancé" - our relationship was progressing rather quickly.

The drivers used a piece of twine to tie off the section of tube with the hole and stuffed the whole thing back into the tire. After an hour wait, we got back on the bikes and headed out of town on the same road we had taken in. At first, I assumed that we had made a detour to get the tire repaired, and we would soon make the turn for the falls, but in the minutes to follow, it became increasingly apparent that we were headed back to the car. The tire went flat again and we had to double up once more; we got stuck in the deepest section of one stream and had to hop in and walk.

Back at the car, our drivers insisted that whatever amount they had agreed to be paid was actually just a tiny fraction of what we owed them. This seemed a bit bold as they had never taken us to the place we were paying them to take us. I dropped a pile of gourdes on one of their bikes and quickly went to grab the car. I suspected they might attack the car as we passed, but they likely took one look at the bruised and battered exterior and reasoned that they could have little effect - and they might give themselves tetanus besides.

|

| Fort at Saint Louis de Sud |

Homeless in Haiti

We set off on the road to Port au Prince having no clue where we were to spend the night. Our flight was at 10 in the morning, so it would make sense to stay in the city itself, but the cheapest room there was $40/night, and there were no particularly desirable locales within an hour in any direction from the airport. Turning onto the road for the south coast, we formulated a plan that involved seeking out a cave and convincing nearby villagers to put us up for the night. This fell apart when it got dark before we reached the trailhead for the cave. I resolved to keep driving to Jacmel and figure out something there.

A downpour started, and this, coupled with the darkness, meant that we could see next to nothing as we turned and twisted along the windy mountain road to the coast. Arriving in downtown, we were greeted with a scene reminiscent of a zombie apocalypse - a huge crowd of people, filling the whole street, raced towards us, as the cars in front of us desperately tried to spin around and get out of there before they were overrun. We did the same and retreated down the road to a milkshake vendor to ask directions and formulate a plan. The city was in the midst of a massive weekly Sunday festival, and so we took backroads to the beach. Since my last trip to Jacmel, the coastline had been transformed into a broad, glittering, mosaic sidewalk with live music, street performers, and hordes of people walking to and fro. We left our car behind a jeep full of riot police, charged with monitoring the promenade, and joined the revelers.

We had reached the main square when it abruptly started pouring. Hundreds of people hid under the pavilion and the playground. We headed for the luxury hotel and ordered a single beer so we would be entitled to stay dry, make use of the sparkling clean bathrooms and listen to a live band. We had forgotten just how disgustingly filthy Emily's clothes were; next to her, I was nearly socially acceptable. Fortunately we were the only ones in the restaurant and the staff had little cause to chase us away; one waitress offered to sell Emily a t-shirt.

We retrieved our car and parked it on the main square away from the street lights. The seats reclined all the way and we managed a pretty decent seven hours of sleep before we awoke at 4am to drive to the airport. It took little over an hour to reach the outskirts of the city, and then another two to make it through the maniacal rush hour traffic to the northern edge of town. All manner of vehicle, from the swarms of tiny motorbikes, to the monstrous frankenbuses, swerved at random between all four lanes on both sides of the road. A water truck sped by, blasting the Titanic theme song over external speakers to let people know their morning delivery had arrived.

The gas gauge was two marks away from full and we pulled into a station and handed our last 200 gourdes to the attendant hoping this would top it off. We started up the car again and the gauge remained unchanged. We looked all over town for a money changer and traded in $5 and stopped at another station and put this in the tank. The gauge remained unchanged. We gave up and returned the car to the rental agency and paid $10 to cover what they estimated to be two missing gallons. We also gave them about 80 leftover sachets of water, which they seemed quite grateful for.

There were still 60 seats available when we reached check-in and the attendant gave us each a "big front seat". We were likely some of the smelliest passengers to ever fly first class.

|

| Random parade of people covered in mud |

|

| From the Orlando school district to the mean streets of Haiti! |

|

| Jacmel's brand new boardwalk |

|

| Carnival central |

|

| Our 60 gourde excuse to duck out of the rain and use a fancy hotel's bathroom |

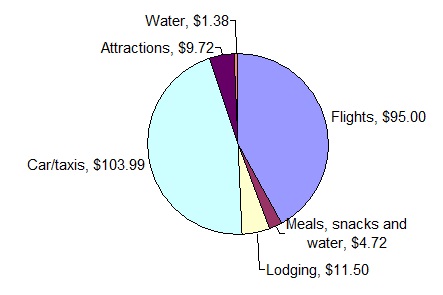

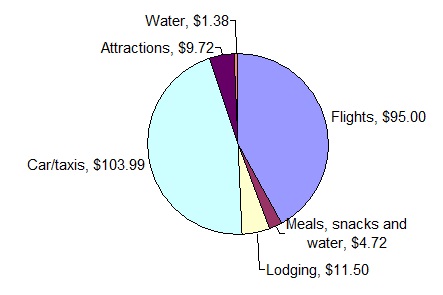

Costs

Taxes for free Spirit flight to Port au Prince: $95

Rental car (Mazda 2) for 3 days: $130

Gas for rental car (750km): $76

Rice, beans, and veggie mush: $1.50

Guide for Marie Jean cave: $5

Hotel in Port-a-Piment: $12

100 bags of water: $1.25

Beer in fancy hotel: $1.50

Coconut water: $.60

Per Person Total: $228