Kazakh- and Kyrgyzstan - August 16th - August 28th, 2016

"Couchsurfing"

For a traveler who typically doesn't reflect upon sleeping arrangements till right around dusk, couchsurfing is not an intentional process. It's usually not possible to search through a long list of hosts and see if your interests mesh, and garner from a set of reviews the probability of that person being a sociopath or serial killer. Your host is the last ride of the night, or the wealthier friend of the village chief, or the guy who notices your backpack as he waits behind you in the takeout line. You don't get to assess whether you'll be sleeping in your own room or if you'll have a bed or a couch. You simply follow your host, by the light of his cell phone flashlight, into a room or a hut. He gestures to a bed, or a mat, or a rice bag emblazoned with the words "A gift from the American people". sometimes there is already someone sleeping there. Sometimes there are three people sleeping there.

But the internet has allowed us to take charge of our own destiny, and learn where we might sleep hours or days in advance, and assess and analyze every minutiae of our accommodation. And this is profoundly useful if you don't want to find yourself wandering through the slums of Port-au-Prince after dark, or believe your travels might benefit from an intelligible conversation. And if I enjoyed browsing websites and profiles half as much as blindly fumbling through foreign lands, I might make use of such a service myself.

But on this particular trip, Maria took the initiative, and when we arrived in Almaty at 5 in the morning, a few of the twenty or so hosts she had contacted the day before had already agreed to adopt us for the night. She followed up with one such host and we arranged to meet his assistant at the Ramstore downtown.

After a Benny Hill-esque pursuit through the multi-story mall, the assistant eventually caught our trio and escorted us to a nearby apartment block. She handed us the keys to an upscale two-bedroom apartment that was to be all ours for as long as we wanted to stay.

Later that evening, we arranged to have drinks with our host. When the agreed-upon time had arrived, he called to inform us that his driver was out front. We boarded a deluxe black SUV and were chauffeured by an affable, though English-less, Kazakh man to the swankiest bar in town. Our host was born Turkish, but was educated in Germany, and had been a major player in Almaty's construction scene for many years. He told us more surfers would be coming through, but we were welcome to stay and share the flat -- or, if it turned out we didn't care for the newcomers, he would gladly give us the keys to another of his guesthouses. After two rounds of drinks and appetizers, and introductions to several friends from the upper crust of Kazakh society, he paid the bill and summoned his driver to return us to our private residence.

In a way, this arrangement lacked a bit of the serendipity and charm of sleeping on a yak skin rug alongside a family of eight in a village yurt. But I did a pretty good job of concealing my disappointment.

|

| Migrating with the sheep |

|

| No need to spring for a translator, you've totally got this! |

|

| Charyn viewpoint |

|

| Sathi |

|

| Possibly the house with the tastiest bread in the world |

|

| Guesthouse's backyard |

Assess your Driver

"Hitching is never entirely safe in any country in the world, and we don't recommend it" -- every Lonely Planet guidebook ever.

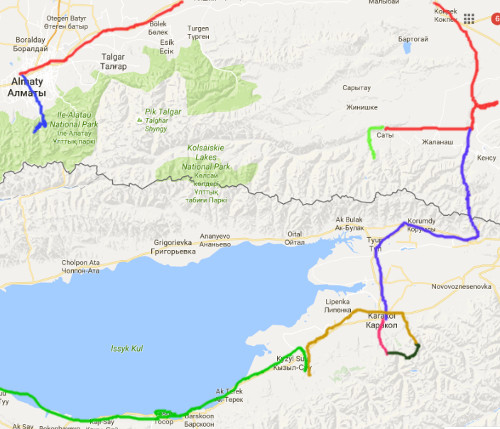

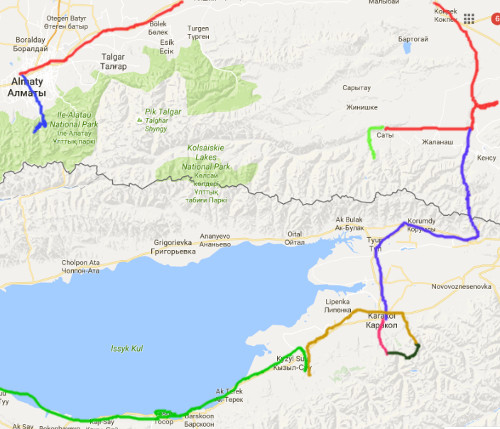

In Kazakhstan, hitchhiking is a way of life. Whether you need to go half a mile across town or 1200 kilometers across the country, you just put out your hand and someone will stop. Women and children will wait in the middle of the night, on an unlit city block, or a quiet stretch of highway, in the hopes of securing a ride from a random passerby. Most drivers expect to be paid, but the price is never particularly high, and many popular routes are fixed. One traveler, attempting to hitch in from the airport, reported turning down twenty-three paid rides over the course of an hour before getting his first free one; he saved $1.50.

My travel companions had a cavalier attitude toward hitchhiking. They had never spent hours on the side of a hot, dusty stretch of highway, watching a thousand empty seats pass without slowing. They saw no reason to split up our group of four, and wouldn't bother to put out their thumbs for any but the choicest rides. Much to my chagrin, they experienced nothing to deter this outlook for quite some time.

To avoid a late, awkward city exit, we went to the bus station to catch the 7am bus to the Charyn Canyon junction, but I was the only one interested in paying the $3 extra for a ride up the 15km dirt road to the start of the hike. We arrived at a lonely turnoff, a hundred miles from anywhere, and started hiking through the desert. None of the others had brought enough water. It seemed likely that at least one of them would die if we were forced to walk the whole distance. Perhaps this was a necessary sacrifice to convince them of their recklessness. Sadly, after only half an hour, a stream of cars turned down the road and the first two vans of tourists picked us up and gave us a free ride to the start of the hike.

With similar ease, we escaped from the canyon and made our way to the town of Sati. Peter and Maria, though staying in a tent in an open pasture, managed to power through five hours of morning sun and sleep till 11, unconcerned that we might miss the Saturday morning tourist rush to our next destination, the Kolsai Lakes. When we finally swaggered out to the road, an ancient Russian hatchback immediately rattled up to us and the driver claimed he was on his way to the lakes. He smelled as if he was about a bottle of vodka shy of sober and it was fairly apparent that he had pulled out of his driveway when he saw us coming, but he was offering a free ride and we didn't see any better options forthcoming. We awkwardly piled in amidst piles of junk; the sharpened edge of an axe rested against my exposed left ankle.

The feisty little car exploded up the rough mountain road. Our driver routinely turned back to us for minutes at a time, unconcerned by oncoming traffic or the curves that threatened to send us plummeting off cliffs. When we approached a herd of sheep, he viciously pumped the gas, aggressively carving a path through the sea of unsuspecting creatures. The left side of the car was tossed into the air, one tire at a time, and we watched as one of the hapless animals limped away behind us. When we arrived at the guard station, we had to get out to buy our tickets, and we took the opportunity to politely excuse ourselves from the proffered ride; our driver begrudgingly turned around and headed back to town.

Our next ride was an off-duty cop. He proved the fact by digging out his badge while his 4-year-old son held the wheel. He took us the rest of the way to the lake, and even got us beyond the traditional start of the hike by flashing his credentials to the guard.

For the ride back to town, we hailed a tour bus. The guide announced us as we boarded and eighty Almaty tourists exploded in applause as we found our seats. This was not particularly conducive to diminishing my friends' bravado.

|

| Not one of the faster rides we got |

|

| One of the Kolsai Lakes |

|

| Why pay $3 for a yurt when you can camp for free? |

One More for the Road

We didn't set out to ruin Valentin's marriage. When he started to follow us to the pub, we figured he would have one drink, then return to enjoy a quiet evening with his wife and kids. Halfway through the mile walk from the hotel, an intense debate erupted over whether the place would actually be open, even though half of us had seen the yawning doors beckoning just an hour before. It was shortly determined that a far safer option would be to buy booze at the grocery and drink back at Peter's tent. Since we were guests in his country, Valentin bought us a round of beers and a bottle of vodka - we presumed the latter was to be shared by the group.

The vodka bottle made many rounds through the group; most of the stops were purely ceremonial, and yet it emptied at roughly the same rate as our beers. When we had finished our respective drinks, Valentin declared that we must return to the grocery; I went for want of cookies, but our Kazakh friend procured another four beers and a second bottle of vodka. We returned to the tent and promptly finished off this second round. Shortly after, Valentin disappeared into the night; we breathed a sigh of relief as we imagined he must have gone back to his family. But he would return half an hour later, inexplicably missing his shirt. He started showing us wounds from battles in Afghanistan and told us about an imminent move to Sarasota.

We decided that it was time to take Valentin home and began an hour-long process of wrestling him back along the dark streets of the village. He would break away and do a few tai chi moves, and rapidly dart to and fro, evading our grasp. When we arrived at his room, his wife met him with a string of expletives and cast a disdainful glance our way as if she held us largely responsible for her husband's condition.

This was a pretty typical night in Central Asia. Another evening, a man arrived at our yurt and offered us a bottle of vodka fourteen times in quick succession, rubbing his belly and patting his head each time. On my final night in the Almaty airport, a group of locals adopted me and bought me cognac and coffee until 4 in the morning, in what disturbingly seemed like a nightly tradition. Shattered were any and all perceptions regarding the quantities of alcohol the human body could endure.

|

| Better maintained than many of the cars that offered us rides |

|

| Hiking the lonely road into Kyrgyzstan |

|

| Consultations with a colt |

|

| Racing the locals |

|

| "I'll have a coffee and something from this list of what I imagine are foods of some kind" |

|

| One of 12 random rooms in our hostel |

|

| Wind-protected campsite by a lake |

|

| One of the neatest church exteriors in the world |

|

| After our host showed us how to tuck in Ewa |

|

| View from the toilet |

|

| An unusually sociable bathroom |

|

| Hitching the next leg |

|

| Private hot spring hut |

|

| Yurt in front of our free campsite |

The Breadcrumb

"There is nothing quite so detrimental to meaningful travel as a well-written guidebook."

A few years ago, it was reported that one or more of the authors of a popular guidebook series had never actually traveled to the countries they had been hired to write about. I suspect the book I took with me to Jamaica was the product of just such a deception. Because of scant, and often inaccurate, details, we found ourselves sleeping in a cage in a semi-abandoned amusement park, then camped next to twin stripper poles in a half-finished mansion, then following a stoned rasta man into the bowels of the earth. It was easily one of my all-time favorite trips.

Too often I'll find myself reading the same page in my guidebook again and again, as if the words of the author form a sacred incantation that must be followed to the letter to have the desired effect. But in the world of travel, nothing could be less desirable than to trace the exact steps of another, and to have all your expectations perfectly met. If you go to Egypt and see the pyramids, but you never trip over a crocodile, or wander lost through the desert, or inadvertently trap yourself in a squat toilet with an old rusted door, it can hardly be argued that you could not have made far better use of your time and money had you stayed home like the guidebook author and spent a few minutes with Google Image Search and Photoshop. If your puzzle pieces all align perfectly, and every border, every hue is identical to what was on the box, your trip was nothing more than a waste of jet fuel.

As we amass bigger and bigger heaps of data, and hone increasingly powerful tools for searching those heaps, we undermine exactly that which makes travel worthwhile. Gaps in knowledge, foolish misinterpretations, hitchhiking in a box truck because you wanted to save $3 on a taxi, shortcutting through a dense tropical jungle -- these are the seeds of a fruitful trip, and woe be to the one who is too rich or too wise to plant them.

It is not hard to find a hot spring in the Kyrgyz valley of Altyn Arashan. Every guesthouse and yurt camp has access to at least one, and it's effortless to slap down 100 som and immediately procure a key to the nearest private shack, complete with tub, shower, changing area, and easy access to an icy cold stream. We found ourselves in just such a pool within an hour of coming off our 2-day trek. But what intrigued me far more than these was a seemingly misplaced pin in the OpenStreetMap data, a mile downriver from our camp, with no roads or trails leading to it, labeled simply "Hot Spring".

As we began our morning walk toward town, I watched our navigational arrow move closer and closer to this point, and at a seemingly opportune moment, I turned toward the river on a rough trail with an indecipherable sign and a dozen flighty cows that acted as if no man had ever passed that way before. The trail morphed into a sketchy cliffside traverse and eventually dropped steeply down to the river. Here, at the exact point marked on the map, I found a carefully crafted concrete log, with a perfect, bathwater spring tucked inside. Further on, down an even less well-kept path lay another pool that had been sculpted into the shape of a frog, and beyond that, a little bit of scrambling and rock-hopping brought me to another that was perched up behind the stalactites of a small cavern. I took a leisurely morning bath and returned to the main trail, never encountering another person on the offshoot, despite the hundred or so backpackers and glampers that currently inhabited that section of the valley.

It would have been easy for me to record the trails leading to these pools and drop descriptive pins at each, and upload pictures, so that anyone with access to this freely available map would at a glance be convinced to visit the springs and be perfectly assured of their success every step of the way. But had I done so, I would have relieved that place of its magic, and it would soon become just another stop on the tourist trail.

And so it remains a whisper of a hint of a nebulous thing. A meek suggestion that more than likely only seeks to needlessly bleed away your precious hours. A single breadcrumb.

|

| Secret log hot spring |

|

| Secret frog hot spring |

|

| Secret cave hot spring |

|

| Free romantic hot spring |

|

| Broken Heart formation |

The Difference between Boulder and West Africa

I recently went on a climbing trip to Upper Dream Canyon, a jungly, heavily shaded collection of rock walls just a few hundred feet above Boulder Canyon, but a world away from the crowds that flock to those crags. "Popular with nudists and homosexuals", read one guidebook, but we saw neither disposition displayed.

On the way out, we passed a beautiful landscape of high desert hills, sparsely populated by million-dollar homes. We mused about what it might have been like had rich people not been allowed to carve out the acreage west of Boulder, and the land had been left to public use. Would it have been peppered in trails that all could enjoy? One friend posited that she wouldn't mind living in such a house, and spend each morning gazing out over the whole of the front range. I had to agree.

My host mom back in Sierra Leone was one of the wealthier residents of our small village of New York. She had a large house with all the amenities - a flush toilet, an unpowered fridge, a perpetually dark big screen TV - and what was perhaps the largest patch of grass in town. But no fence surrounded her property, nor was it walled off by any implicit sense of exclusivity. Every kid within half a mile played in that grass, and pedestrian trails criss-crossed the yard, connecting the village and creating a meeting place for anyone and everyone to stop and chat. My host family cared for at least four small children in addition to its own, and these ran wildly about the house. The family next door had one of the only electrical connections in town, and each evening, a dozen neighbors would sit on the couches and charge their phones on the daisy-chained power strips while watching terrible Nollywood films. Our neighborhood was made up of both Mendes and Temnes, both Christians and Muslims; there were no declared homosexuals or nudists, but many did shower in their front yards and hold hands with those of the same sex.

Much of my time in Guinea was spent stumbling into small villages and farms, sun-baked and badly dehydrated. I walked right through people's yards and often across their front porches, because in West Africa, that's where trails go. I never encountered a locked gate, barking dog, or belligerent resident. Rather, the children would immediately be sent into the family's orange tree to pick 20lbs of the choicest oranges, and a large pot of tea would be prepared. They must have surely guessed that I couldn't carry away 40 oranges in my tiny pack, or drink a gallon of tea in a sitting, but they would bring them all the same.

|

| Airing out the yurt in the morning |

|

| Almaty: The Paris of the East |

|

| Bee boxes |

|

| Pre-fab beekeeper trailer |

|

| Bus stop |

|

| Beach |

|

| Loungest next to the world's second largest alpine lake |

|

| If you're tired of that renegade biker look, here's an easy mod to make you and your bike a lot more approachable |

|

| Charyn Canyon: The Grand Canyon of Central Asia |

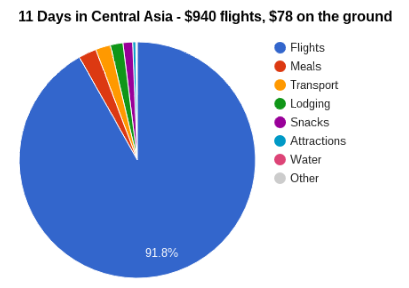

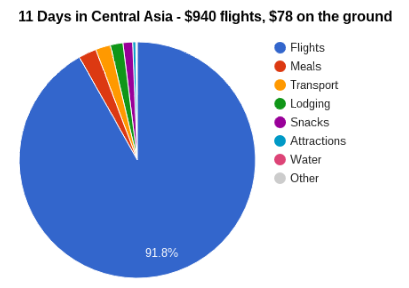

Costs (US$1=343 KZT, 68.5119 KGS)

Cheese or meat/cabbage samosa: 90 tenge

6L water: 176 tenge

City bus (including airport and mountains): 80 tenge

Almaty museum entry: 500 tenge

Share of taxi ride to Charyn Canyon: 2000 tenge

Village guesthouse bed: 2500 tenge

Village guesthouse meal: 1000 tenge

Cup of horse milk: 12 som

Sim card with 1-week of service, 3 gigs of internet, 200 mins, 200 texts: 100 som

Bed at Karakol hostel: 200 som

Yurt stay: 200 som

Meal in market restaurant: 100 som