Tackling the trail in the morning after the rains

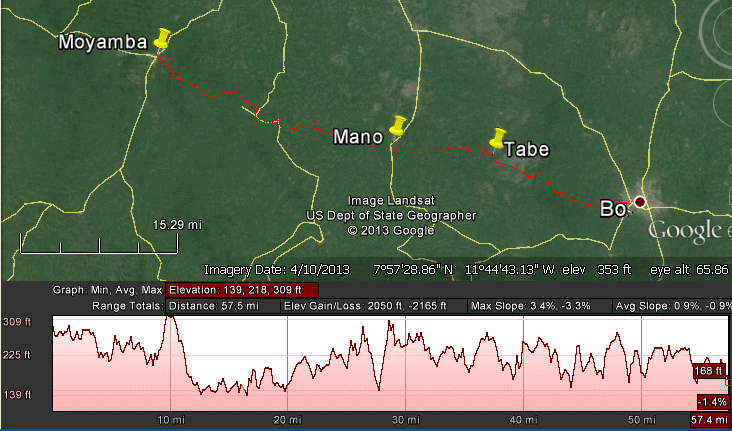

| Mi. from Bo | Mi. from Freetown | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | XX | Bo-Kenema Highway and Mattru Road Intersection |

| 6.9 | XX | Kudiama Village |

| 10.2 | XX | Sembehun Junction |

| 11.9 | XX | Kakama Village |

| 16 | XX | Tabe Village |

| 17 | XX | Leimema Village |

| 20.4 | XX | Salina Village |

| 21.6 | XX | Bendu Village |

| 23.2 | XX | Gbodumma Village |

| 25.2 | XX | Semabu Yessa Turnoff |

| 27.3 | XX | Mano Town (Trail overgrown after bridge, detour with hills, dirt road with no cars) |

| 29.2 | XX | Kortahun Village |

| 30.9 | XX | Nitty Junction (Rejoin trail here) |

| 33.5 | XX | Mogbaseke Village |

| 37.2 | XX | Mokaba Village (trail overgrown ahead, must take detour, downhill ride to highway) |

| 40 | XX | Intersection with Highway (60mph traffic with lots of dust - about 5 cars passed in 3 miles) |

| 40.5 | XX | Mokpakpayagbe Village |

| 43 | XX | Kangahun Town (Highway ends here, no more cars) |

| 45.1 | XX | Bpatema Village |

| 47.8 | XX | Bambuya Junction |

| 51 | XX | Levum Village |

| 51.4 | XX | Gbonjeima Village |

| 54 | XX | Lunge Village |

| 57.1 | XX | Moyamba Town |

"Are you going to invite me to eat?", a man asked as I shoveled down a plate of rice and beans. Even though I was hidden away in the tiny thatch hut, my presence had drawn a crowd. I reached into my pocket to power on my phone as I introduced myself and explained my mission to each new person that arrived. I tried to hold my composure and stay engaged as chimes sounded repeatedly to notify me of one new text message after another. I didn't want to read them; I hadn't wanted to turn on my phone at all.

In my inbox were a number of messages from Alaaka, the security guy, Daryn, the interim country director, and several of my fellow trainees. "Please report your location." "Call immediately." The jig was up. Somehow my plan had been leaked.

Daryn spoke to me as one might speak with a jumper who was poised on an eave on the 30th story, threatening to take the plunge and end it all. He made no strong accusations nor hinted at any punishments but, in a tone that pre-supposed my compliance, stated that I must immediately veer from my course and go north to Moyamba Junction where I would be met by a Peace Corps jeep.

The storm had just skirted Moyamba and now I could see clear to Freetown, 50 miles to the west. It is rare during the rainy season to see anything of the sky, but the remainder of the trail lay under a brilliant blue, playfully speckled with a few wispy clouds. It was only 1PM and I still had six hours to ride; I could stay in any one of a hundred small villages on the way and complete the final stretch to the highway first thing in the morning and choose from the steady stream of buses that would be plying the main route to Bo. But this was no longer an option. I turned towards the junction and into the storm; the ominous clouds ahead were the perfect metaphor for my downtrodden spirit, and for my nebulous future with Peace Corps...

I arrived home from village day just before 5:30 Friday, and downed my waiting dinner. I had packed my bike that morning and now dragged it outside. "I'm going to Freetown", I told my host mom. She did a double-take. "I will be staying tonight in Tabe, and will continue on and stay in another village tomorrow, and will return by bus on Sunday afternoon." She was struggling a bit to process this; two weeks before, I had talked with her at some length of my plans, my motivation, and why I was well-equipped to tackle such a challenge, but it was a gross departure from the African mindset. "Does Peace Corps know?" Avoiding any direct response to the question, I answered "I emailed Daryn about it." This was true. I failed to mention that he had never replied. She voiced a reluctant acceptance and I went on my way.

I had borrowed the bike from Daniel who had ridden it back from his site visit. It was a Peace Corps-issued Trek 820 in good condition. We weren't supposed to have access to these for another month. I had a pump, a toolset, some patches with an empty glue bottle, and an extra tube with a hole in it. Using only my bag's straps, I had attached all my gear and water to the back rack; I would be chasing my water bottles after every bump. I knew I had to reach the village of Tabe, 16 miles away, by nightfall; one of the Salone 3 volunteers had informed us that spitting cobras frequented the bush paths at dusk.

Matt and I had taken the old railway line to Tabe two weeks before. It was very smooth and level dirt single-track through jungle, savannah, and rice paddy. The scenery was spectacular and the villages along the way were amazingly welcoming. Friday night was all about speed, however, and, aside from the precarious log bridges that I walked across, I was able to cruise at around15mph.

I crossed the Tabe river and entered the village shortly after sunset. I picked out a random hut and asked where I might find the chief. "I am the chief". What are the odds. After a brief chat over groundnuts, the old man left to secure for me the finest room in town. I headed towards the other end of the village to speak with a man we had met on our earlier visit. I checked my phone and found a few birthday texts; there was no coverage in the village, so I switched it off.

Julius Quee is the great-great-grandson of Tamba Quee. Tamba, as a regional tribal leader, had signed an agreement with the queen in 1890 that put him in charge of a vast territory. Julius proudly produced his copy to prove this fact. To this day, anyone who wants to develop any of the land within the dozens of surrounding villages must first get Julius' blessing. His daughter was the paramount chief of the chiefdom. He was a photographer before the war, but was old now, and only dabbled in farming and served as ambassador to any foreigners that might turn up; there had been 3 in the past two years.

My accommodations were an apartment with a locking door and a king-sized bed. The bathroom was a primitive pit latrine with bats roosting inside. The owner was staying up all night to pray at the mosque for the final days of Ramadan, so the timing would be perfect. My stay was free, as it would be anytime I decided to return, as were any meals I wanted prepared while I was there.

Were there other places like this left in the world, where you show up at dusk to any random village and receive the royal treatment at no cost? My plan was to bring eco-tourism to Salone, but that would surely mean spoiling this spirit of selfless giving. I would need to tread lightly.

The muzzein droned the whole night but intensified around 5am and was joined by the repeated sounding of a loud brass gong. This was no village for sleeping in. Just across the street, a group sat in a candle-lit hut, chanting melodious hymns in the pre-dawn haze. An old man hobbled along the main drag, singing wistfully to himself. I went to say goodbye to Julius. I declined several offers to have his wife start up the fire and cook whatever I felt like eating. He added shoelaces to my rigging to give it some shot at surving the road ahead, and sent me on my way.

It had rained heavily the night before and the narrow path through the head-high grass was lined with puddles. But the trail was solid and I made fast progress through the string of villages leading to Mano. Here, it was the monthly cleaning morning and police patrolled the streets to arrest anyone found moving beyond his/her yard. The cookery shops were unmanned and there was no food to be found. In the next village beyond the river, I found a woman selling cassava bread and pepper sauce. I said I wanted 500 leones worth, but she looked through her stash and explained that she only had 300 (7 cents) left; I managed to eat half of this before I was full.

The railway was overgrown after Mano and I followed a good dirt road through rolling hills. I happened upon the district counsellor for the area and he gave me his number and pledged to order the path brushed (machete'd) whenever I should say the word. In Mogbaseke, I met the man who had moved into the old station house soon after the trains stopped in '73 and had lived there ever since. A few miles further, after Mokaba, the trail was again too bushy to ride and I had to make a lengthy detour downhill and in roughly the opposite direction. I passed through a bog replete with wildlife; several thin maroon rodents raced across the road and a zebra-striped bird with a long flowing black tail briefly hung suspended in the air before me. The only available alternative is a new super-highway where cars and okadas hurtle through at slightly insane speeds, spraying up dust and rocks and diesel fumes. In the 3 mile stretch, I would see 5 cars – this was 5 more than passed by in the remaining 54. This was a sad testament to the effect of development on Salone's fantastic hiking and biking treasures. I would have to act fast.

After Kangahun, I was again on empty dirt track all the way to Moyamba. At one point, the children's calls switched from "Pomuy" to "Opotu"; I had entered Temne land. My Temne was even worse than my Mende but still I greeted every single person I passed. I must have delivered some 800 greetings in a 6-hour span. I met an old man in Levum who spoke in glowing terms of a Peace Corps volunteer by the name of Matt Barrons who had been there in '83 and had built the town school. He reminisced about the days when the train used to follow the route prior to its dismantling.

I can't even approach an adequate picture for the magic I felt following the ghost of the railway through the bush of southwestern Salone. The path was typically excellent, lined by vistas, imbued with the smell of flowers, perfectly shaded. It was punctuated by clever bridges made of logs or train parts, the ruins of old stations that had been filled with homes, hospitals, and supply stores, and an endless supply of quaint thatch hut villages. Everyone I met was absurdly happy to see me and receptive of my mission and ready to provide whatever I needed and talk for as long as I wanted. In every village, someone spoke perfect English and had fascinating stories to tell...

The rain poured and the puddles grew as I followed the 22 mile stretch to Moyamba Junction. I fished my phone out of my dry bag to learn that the logistics officer had reached the junction and I told him to meet me en route. A man in army fatigues on a dual sport stopped beside me and asked "Are you the one they are looking for?" He was a church pastor, apparently, and was one of the search parties that had been deployed across three districts. I informed him that everything was under control. The jeep met me and we lifted the bike, caked with several pounds of mud, into the back; my 'rescuers' were hired guns – a driver, a language teacher, and a security guard – they could care less about Peace Corps' senseless conniption and applauded my adventurous spirit. I got a few more calls from concerned fellow trainees who had not yet been notified of my capture. What had happened in my brief 16-hour absence from this weekend free of any scheduled events or other obligations? Who had ratted me out? The missing pieces of the story would slowly be pieced together in the hours to follow.

Friday night, a VAT (current volunteer assisting as a trainer for the week) had called my host mom to check up on my progress on assimilating into the family. She had said something to the effect of "Don't you know? He's on his way to Freetown." For whatever reason, the volunteer forwarded this intelligence to the training director. He immediately flipped out and attempted to follow the rail trail as far as he could with a jeep, checking the rivers for my body, and questioning the children en route about the Pomuy that had passed earlier that evening. He was out until midnight and, in the process, notified all the police departments within a hundred miles and various other parties. He would spend the entire morning running about, sending distressing messages to trainees and everyone else under the sun, and generally causing a panic.

The trail is an amazing treasure that could be a huge boon to the country's fledgling tourism industry and a life-changing experience for anyone who rides it. I hope that some day it becomes accessible and helps to prove to the world just how ridiculously fantastic Salone is.

Tackling the trail in the morning after the rains

Old Bendu Railway Station

Mysterious jungle piglets