The ubiquitous liquid breakfast carts

*Most of the better pictures on this site are thanks to Andie, but if you want a more complete collection, check out her site here.

Christmas came especially early this year, as the school administrators had opted to chop a week off our already piddling winter break and tack it onto the week between summer and fall. I would probably resent them for this come mid-December, but for now it seemed the perfect chance to take the much awaited free trip to Peru.

Now that Spirit had gone to great lengths to convince the world that you couldn't reach them by phone, all I had to do was fish their 800 number out of an email from a year ago, and within seconds I was patched through to an enthusiastic call center employee in Mumbai. He took my voucher number and travel dates, fed them into his console, and cheerfully announced "That will be 1500 dollars!" I took a moment to digest this and meekly questioned "…but I have a voucher?" and in the same boisterous tone he resounded "But you have a voucher!" Suddenly his eyes lit up (rather, I can only infer that they did from his pitch, given that it was a phone call) "Would you like a Big Front Seat, sir?" (this is Spirit's equivalent of first class, but doesn't imply free drinks or foldable TVs, just that your seat is bigger than everyone else's and you can be the first one to dash off the plane for the Customs line); after confirming that this too would be covered by my voucher, I responded in the affirmative. "That will be 3000 dollars!" It was now clear to me that this man was working on commission, but I was a little perplexed as to how he reached this sum, since the same seats on the website cost under $1000. I paid $170 in taxes for the two of us - I had kind of been hoping that the seats would be completely free, but for two first-class, high-season tickets from Orlando to Peru, it seemed a reasonable fee.

I had scheduled my exam for the Wednesday of finals week so I could be sure to have everything squared away in time to leave that Saturday morning. This turned out to be largely unnecessary since, by that time, I had scared off the majority of my students and I was able to grade the papers of those nine who remained in under an hour. I spent the remaining days cleaning up the mountain of trash that had consumed my apartment in the months since I lost my compulsively neat roommate to a summer internship at IBM. I cleared away the macabre display of cockroach bodies that littered the kitchen counters; I had hoped these would discourage the remaining hordes from frequenting my food cabinets, but still, whenever the lights went on, half a dozen black forms would dart in every direction. I would leave this problem for my roommate to resolve; they would probably be twice as big by the time he arrived and therefore be easier to spot and deal with.

I had arranged with my cousin Piet to leave my car at his place while we were gone. He seemed genuinely surprised to see us when we rolled in and woke him up at the crack of noon, but still was kind enough to take us to a neighborhood slices-the-size-of-your-head pizza joint, and drive us to Orlando International. Contrary to what I'd come to expect from MCO, we got through both ticketing and security in under 10 minutes and we had a nearly on-time departure for our 35-minute flight to Ft. Lauderdale. It was not until the 6-hour leg to Lima that we discovered the horrible reality of the big front seats: they were virtually impossible to sleep in. True to their name, they were humongous, and we spent the better part of the flight swimming around in them, trying to find a comfortable position, but it was rather akin to trying to sleep in a large, featureless bowl.

We arrived around 2am and set about finding onward transport. A plane to Cusco cost $173 one-way, so we quickly settled on the 30-hour bus ride. Not wanting to venture onto the dark streets of 8-million-strong Lima, we opted to wait in the food court until dawn; here we found hordes of dirty backpackers, dressed in colorful Incan clothing, lying all over the floor, but since we had neither the comfort of sleeping bags, nor the protection of a large group, we simply sat awake at one of the tables. The tourism counter lady refused to tell us anything about the bus going into town; we tried to find it ourselves, but were bombarded by taxi drivers and eventually resigned to just pay the five bucks to be taken directly to the bus station.

The long-distance bus situation in Lima is the worst imaginable; a few dozen companies run to a variety of destinations, but they all do so out of private terminals which are scattered throughout town (inevitably in poor neighborhoods). The result is that you need some prior notion of bus schedules and prices, but since there's no central repository for this information, the only way to get it is to call or visit each company. We inquired at the station to which the driver delivered us and found that the next bus was at 8:30AM and cost $15; this was 2 hours later and $9 more than we would have preferred, but there seemed to be little we could do about it. While we waited, we hit up a few nearby food vendors for a scrumptious yam sandwich, as well as a decidedly less tasty head (perhaps cow or sheep) and hominy soup.

To the uninformed observer, the countryside surrounding Lima appears to be a desert wasteland with no plants, animals, or water, and be wholly incapable of sustaining life. Nevertheless, millions of people have constructed mud or thatch shacks amongst the rocks and sand, and seem to be having some success at surviving, despite an obvious lack of all the essentials. Had I been shown pictures of this place out of context, I would've insisted that it was North Africa, the Middle East, or the far reaches of Kazakhstan, but never could I have guessed that it was part of one of the most biologically diverse countries on Earth.

Our "luxury" bus lacked the complementary massages and live band that you would perhaps expect after paying $15 for a quick 9-hour ride, but they did supply us with ham sandwiches, cake, and some Inca Cola. First on the entertainment docket was a man who gave a long speech from the aisle and handed out free samples of some product with pictures of intestines on the box (we declined ours). This was followed by an American blockbuster from the 80s and an Incan slapstick film where a tourist from the country falls victim to the myriad dangers of the big city (such as strangle-mugging); the rest of the bus laughed knowingly, while we began to feel a bit of apprehension for our imminent wanderings through the mean streets of Peru. We had been handed little plastic baggies at the start of our trip, but had assumed these were for the disposal of our snacks; we discovered the intended use when we hit the final hour of mountain curves - Andie made ample use of the onboard W.C. during this stretch.

Arriving in Ayacucho shortly before nightfall, we found an immensely lively and friendly city; we followed the masses up and down the pedestrian concourses, ate alpaca at a fancy restaurant, and visited artisan shops with purses made from stuffed guinea pigs and planes sculpted from animal bones.

The ubiquitous liquid breakfast carts

Just in case you've lost a remote or twenty in your couch cushions.

By the end of the trip, each of these pictures would seem completely plausible

Ladder set up to look into the women's bathroom in our hotel

At our lunch stop 3 hours into the trip, we discovered that our bus driver was in fact a chicken...

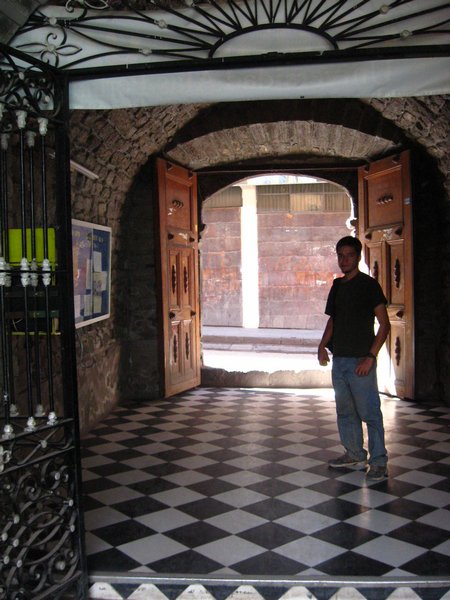

Ayacucho is a picturesque colonial city ringed by high desert mountains. Non-descript stone walls give way to unpredictable worlds beyond. Small wooden doors serve as portals to botanical gardens, maze-like markets, and ultra-modern offices. Pedestrians, motorized rickshaws and livestock all vie for right-of-way in the narrow, often winding cobblestone alleyways that pull the city together.

Like in any self-respecting third world country, markets here are truly an experience. Even in a place as devoid of foreign tourists as Ayacucho, the central market has every handicraft imaginable, including a hat made from the body of a viscacha, a half-rabbit, half-squirrel creature that is quite possibly endangered. There are the usual aisles of fruits, breads, butchered animals, and hot meals, and the town's market was invariably our first stop to stock up on cheap snacks. My favorite feature, however, which is present in every market in Peru, regardless of the size, is the smoothie row. As you approach this row, between three and thirty women will begin to shout offers and try to differentiate themselves from all the other identical vendors. For sixty cents, you can get a blender-full of smoothie, containing virtually any fruit or combination of fruits (and carrots, aloe, honey, vanilla, milk, etc.) you can imagine. If you've ever attempted to drink a blender-full of anything, you know it's a bit much, so it's usually best to bring a friend.

On the subject of market aisles/rows, it's interesting to note that every commercial entity in Peru occurs in a row. You will never see a furniture store, food vendor, or veterinarian by itself - it will always be accompanied by several other identical businesses. It's completely impossible to differentiate the products or services of any one entity in the row from any other entity, and the prices are typically the same throughout. This has the advantage of ensuring that there is always ample competition; if you don't like the price at the first place, you can simply continue down the line until you find the bargain you're looking for. The downside is that you inevitably have to go to the other side of town to find whatever you seek; rather than evenly distributing themselves throughout the various neighborhoods, every single store that sells what you need is located in one remote location.

A set of Huari ruins lies about 15km out of the city. These are rather extensive arrangements of stones amongst the cactus from a city that sat here a millennium ago, and there's even a spot where you can swing down a ladder and enter some small, dark burial chambers (they removed the mummies some years back). In one of the more remote sections of the ruins, we came face-to-face with a sizeable wild boar, but he seemed as ready for a confrontation as ourselves, and we each went our separate ways.

The main attraction of Ayacucho is a set of 33+ churches, most with extraordinary facades, interiors, or both. We had imagined spending the day making a circuit of these, but soon found that the opening hours were arbitrary and unannounced. The few we did sneak into during the 7am Mass had exquisite statuary, and shrines coated in gold leaf. The town's most enticing museum had been turned into a bank and the rest had quite unintelligible themes, so we spent the better part of the day just wandering down random streets and seeking out cultural oddities wherever they could be found. An extensive search for the baked guinea pig delicacy returned no results, but we did find a place serving up tasty and filling three-course lunches for approximately 85 cents. The usual abundance of street vendors yielded such treasures as roasted corn porridge and purple oatmeal - Andie, though always claiming to be starving, would inevitably produce some nonsensical excuse as to why she couldn't eat whatever food I picked out, so I was quickly stuffed with double portions of a myriad of culinary experiences. With no corner of the city left unexplored, we plopped down on a bench in the central plaza and watched a man in a dinosaur costume walk laps around the fountain while handing out candy to the parade of children who fervently pursued him.

The treatment of Peruvian children comes as a great curiosity for members of a society that won't allow a child to leave a parent's side until he/she is twelve, and often keeps a tight tether of one form or another until said child leaves for college. Here, it would seem the universal age of autonomy is three. Toddlers can be seen traipsing down the streets alone, buying ice cream, taking taxis, and more or less acting as full members of society, at all hours of the day or night. You feel a bit silly the first time you negotiate a price for a snack with a diaper-clad vendor, but soon enough you find yourself wondering why all those free-loading babies back home don't get out of their cribs and do something with their lives.

We grabbed an 11-hour overnight bus to the town of Andahuaylas some 200km down an unpaved mountain road. We slept for about two hours before being awoken by an unplanned bathroom break. It seemed a truck had left its log trailer in the middle of the road and the company's three buses (the only vehicles on the road that night) all sat in a row while the drivers brainstormed. The decision was to have everyone get off, leaving only the driver's life in danger as he painstakingly guided his bus between the trailer and a sheer 200m drop. So we sat in the cold darkness for a good 20 minutes while the first bus coaxed its away along the precipice, a dozen helpers standing on either side and shouting out the next move. A cheer went up when it cleared, but a wave of resentment settled over us as that bus loaded all its passengers and drove off into the night. It was now absolutely critical that neither of the two remaining buses fall off the cliff, as there was no way we were going to fit the 110 passengers on just one. Fortunately, both of the vehicles cleared in the next 40 minutes and we could return to our original seats. With no further stops, we arrived at our destination just after dawn; we gave serious thought to jumping on the next day bus to Cusco so we could avoid using our atrophied limbs that had been rendered useless by a long, painful night with 6 inches of leg room.

The rooftops of Ayacucho

Delicious breakfast of lentils, rice, egg, bread, and herbal tea - about 60 cents

Wuari Ruins

She wasn't really taking a picture of me - this was just a clever ploy to get a shot of the old indigenous market worker behind me.

Rice and vegetable oil - two staples featured in overabundance in virtually every meal.

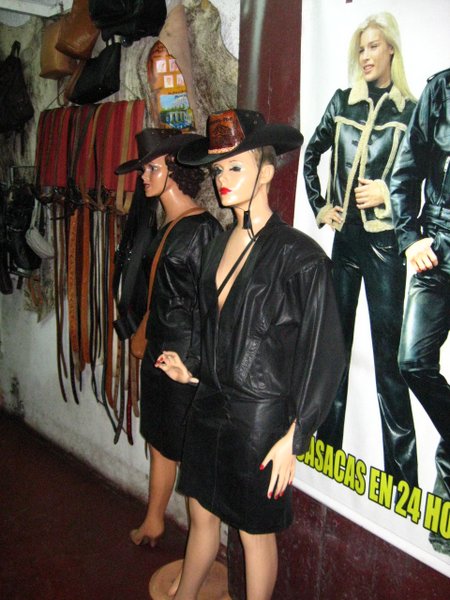

Scary white manicans that seem to show up everywhere.

Behind one of the many portals of Ayacucho

Perhaps Jesus and his disciples didn't have guinea pig for the Last Supper, but if they'd been Peruvian, they certainly would have!

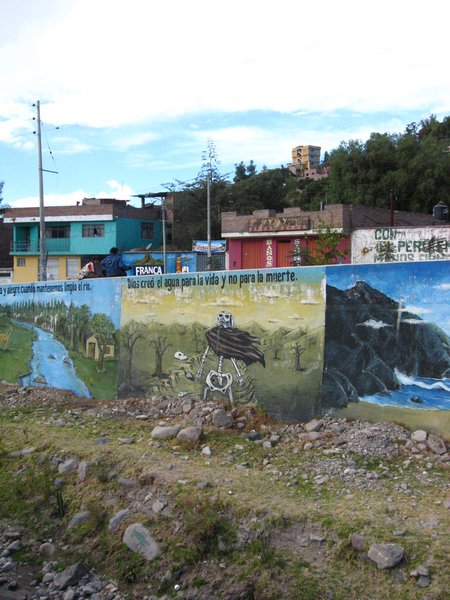

Environmentally conscious murals

Andahuaylas had approximately one sight on offer, the aging, tin-roofed cathedral. With our sightseeing out of the way before 7am, we scouted out some breakfast. We had high hopes for a "vegetariano" restaurant which we happened upon, but this turned out to be just an over-priced health foods store; for the price of two generous meals anywhere else, we got two tiny sandwiches and two cups of something called kiwichi - drinking this is something like imbibing old gym socks.

The owner of the restaurant directed us to the colectivo buses and we took an hour-long ride to the ruins of Sondor. These were downright incredible - not from an architectural standpoint (they were just organized piles of rocks) - but like most of the ruins we would see in the days to come, they were perched upon a high mountain and surrounded by a collection of even more majestic peaks. We went to the woman who had magically appeared to collect a 60 cent admission fee, and asked her whether there were any good hiking trails nearby, but she was of no help in the matter. So we hailed an already overloaded bus bound for town, and made two invocations of the "always room for one more" rule; I straddled the stick and Andie added herself to a pile of colorfully dressed indigenous women.

Back in Andahuaylas, we soon proved what we had earlier suspected - there was absolutely nothing to do in the town. We spent a few hours wandering up random hills and eating miscellaneous things (sadly we discovered a restaurant serving guinea pig immediately after eating somewhere else). We arrived at the cathedral just in time for what we believed was a weekday Mass - it was not until they carried out two coffins at the end of the service that we began to suspect otherwise. What seemed truly strange to us, even when we believed it to be a normal Mass, was that the children (of which there were many) were given free reign to do whatever they wanted - this included running up and down the aisles screaming, eating ice cream, and boxing with their compatriots across the pews - all the while, the other attendees pretended like they could actually hear what the priest was saying over the din.

Just when we had nearly resigned to sit in the park and pass the remaining hours people-watching, we made a discovery to rival anything we had seen on the trip thus far. A nearby playground, which held a Temple-of-Doom-style rope bridge and two hand-powered Dumbo-esque rides, was also home to the most treacherous piece of playground equipment imaginable; a spiral staircase rose about 50ft to the top of an aging super-fun-slide, which went nearly straight down and ended in a brick wall. Swarms of kids of all ages slid down, climbed up, fought other kids, and came within inches of falling to their deaths. What a shame it is that, these days, American children must grow up without such contraptions to occupy their time…

The restaurant that had served cuy for lunch had apparently met with such high demand that they had none left for dinner, so we had to settle on grazing among the myriad food carts scattered around town; in the end, we got three skewers of meat, a bowl of baked apple porridge, 4 scoops of ice cream in two cones, a slice of cake and a piece of apple pie for a grand total of $1.50. We opted to pay a buck extra for the deluxe bus, which meant we got a stewardess who served us hot tea and croissants (but only before we left, since we were still driving all night on unpaved roads and this, sadly, was no hover-bus). The movie for the night was "Nickelodeon Presents: Shredder Man Rules" which reaffirmed my earlier suspicion that the average Peruvian has the sense of humor of a ten-year-old - fortunately it was completely in Spanish and could be easily ignored.

Adobe outhouse

Peruvian tuk-tuk

Hand-powered helicopter ride

Towering super-fun-slide of death.

Andahuaylas waterfront

We arrived in Cusco at 4am, and having spent the last two nights on buses, smelled bad enough for most of the touts to leave us alone. After resting in a stupor for a few hours, we set out at first light for the center of town. Shortly after starting, we spotted a playground that surpassed even the one from the night before - it had multiple towering slides, a hand-powered carousel, and a resident llama.

We spent a few hours trying to find the market, constantly having to reestablish our bearings, being easily distracted by the city's cobblestone streets, extravagant churches, and enticing plazas. Much to our surprise, we were able to find a hole-in-the-wall, in the gringo-saturated town, that served delicious food at prices comparable to those found in the rest of the country. We followed that up with yet another giant 60-cent smoothie.

We stopped at a pitiful little museum to pick up the $25 (doubled in price since my '07 guidebook went to print) tourist ticket; this is, in effect, admission to a multi-city scavenger hunt, filled with ruins, museums and other attractions. The first stop on the ticket was an uninspiring contemporary Andean art exhibit at a government building down the street. We searched at some length for a cheap hotel, but finding none, resolved to stay in a nearby mountain village.

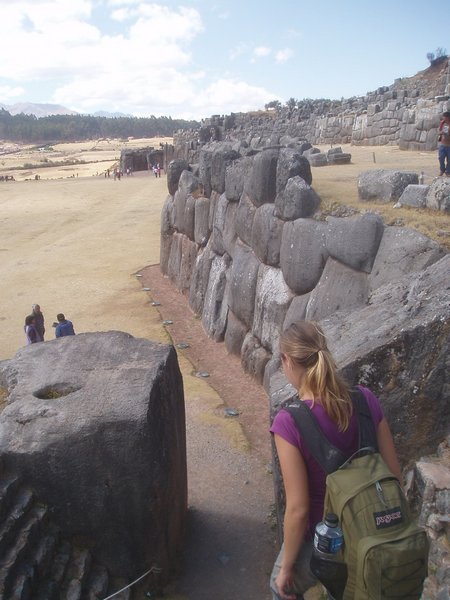

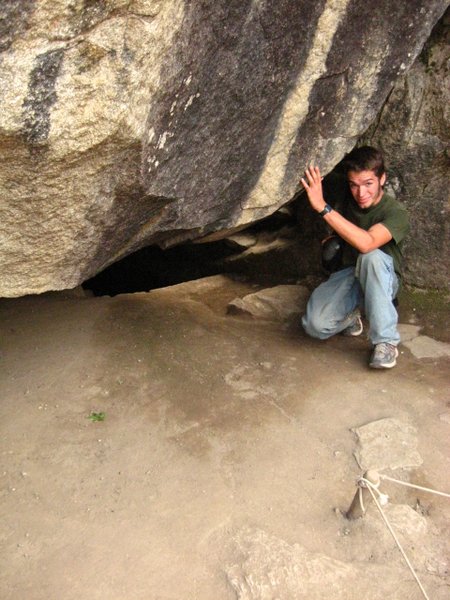

There are a plethora of archaeological sites surrounding Cusco; the guidebook suggests taking a bus to the highest one and walking downhill back to town, but this seemed entirely too easy, so we instead hiked straight up a steep staircase to the first massive site (the spelling of which alludes me, but it's pronounced "sexy woman"). After a great deal of scrambling around the sophisticated structures and climbing the neat rock formations, we went on to seek out a "massive limestone boulder" with labyrinthine stairs and other strange designs carved into it. We found two such boulders and examined them for some length, but it was only the third (Q'enko) that was on the official route.

We were far too exhausted to hike the 4km uphill to the next set of sites, so we took a bus to Tambomachay, where a fountain had been sculpted around a spring, and Pakopakura, where a large red fort overlooked the valley. A second bus brought us to the friendly little town of Pisaq, which sits next to a river between two elaborately terraced mountains.

Walking to the main square, we found the tiny ville to be in the midst of what was perhaps the largest craft market either of us had ever seen. It was clearly possible here to find any souvenir we could conceive, but the daylight hours were waning, so we secured a room at a guesthouse and raced up the towering mountain just beyond. It was an arduous 3km climb to the start of the ruins; we followed ancient stairs up the terraces and edged around grazing bulls that shared the narrow path with us. It was at the first of a series of turret-like structures at the base of a 200-step staircase that Andie declared she could go no further, so she stayed put with the food and jackets, and I jogged up the staircase to what I perceived to be the whole of the ruins. What I progressively discovered was that the ruins just kept going, and I followed them for several kilometers. I ran from one structure to the next, telling myself that I would turn around at the next peak or bend, but there was always something else that caught my eye. After some time, I reached a cave tunnel, and passing through, beheld many more immense fortifications, as well as a line of buses which were piping tourists onto the trail from a road far below (which would've been a great alternative to our round-trip hike if one of our guidebooks had thought to mention it). Here, I turned back and raced down to where I had left Andie, but she was nowhere to be found. I presumed she had left with a group of European tourists (Americans don't visit this site - too much walking), so I stumbled down the mountain in an effort to catch up to them. After a time, I heard a distant cry from the initial fort - Andie had grown bored and gone off to explore the ruins on her own. She eventually caught up with me and we made a rapid descent, though we had to wait several times for the bulls to progress down the stairs.

Back in town, we made a determined search for a cuy dinner, but even in this village which was touted as the home of miniature guinea pig castles, none of the little critters were to be found on the menu. Whilst wandering down the main drag, a gringo popped out of a restaurant to sing its praises, and for a buck each, we got a nice little soup, steak and herbal tea combo.

Playgrounds are for llamas too!

Some art museum

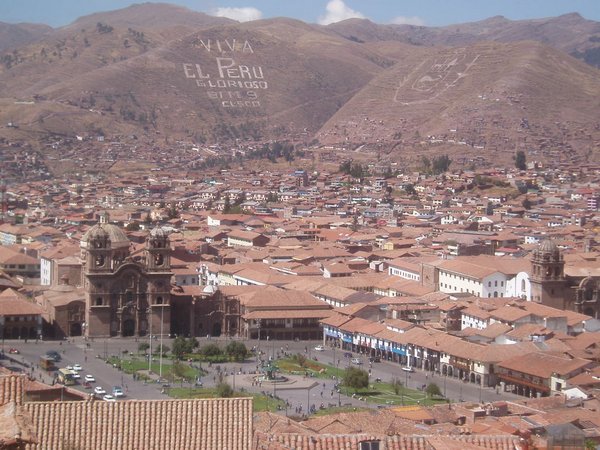

Cuzco

The first major set of ruins is only a 1km walk up out of the city.

Part of "Sexy Woman" ruins

Baby alpaca

Pisaq market

Bull grazing on the Pisaq terraces.

We had been deeply concerned when we returned to town and found all the market vendors fervently disassembling their stalls in the hours after nightfall, but when we awoke the next morning, we found the same people rapidly reassembling the structures they had worked so hard to tear down just hours before. They seemed to care little for us, obviously setting their sights on the first tour bus of the day that would pull in a few hours after we left.

Peruvian breakfast is a meal that we never got a good handle on during our two-week stay. First of all, despite the fact that the sun comes up at six sharp, no one even thinks about eating their first meal til half past seven. Secondly, of the three types of food available, none really quite jive with what I've always perceived breakfast to be. The most ubiquitous option is always soup, usually containing a piece of an animal's head or some other equally disturbing parts. The second-most common is a hot drink made from quinoa; this, "the gold of the Incas", supposedly has all the nutrition of a meal in a single grain, but since it comes in drink form, it instantly fails the most basic criteria for "breakfast food". The final option is dinner food; dishes such as "lomo saltado", a fajita with french fries and rice, are listed on every "desayuno" menu in the country; while these are plenty tasty, they don't fit the bill as a cornflakes replacement. Oatmeal, interestingly enough, is hugely popular, along with roasted corn porridge and purple apple goo which are of similar consistencies, but these are only available for dessert.

Needless to say, we were starved for a decent breakfast in the quiet streets of Pisaq. We found a line of bakeries with enormous furnaces and bought several loaves of bread fresh from the oven. These bakeries doubled as guinea pig farms - in one we found a three-tiered cuy mansion, and in a second we spied a woman cleaning one for lunch. Eventually a stall opened up to serve rack of lamb and beef stew dishes, and nearly everyone in town flocked to it. We got one of each for under $2.

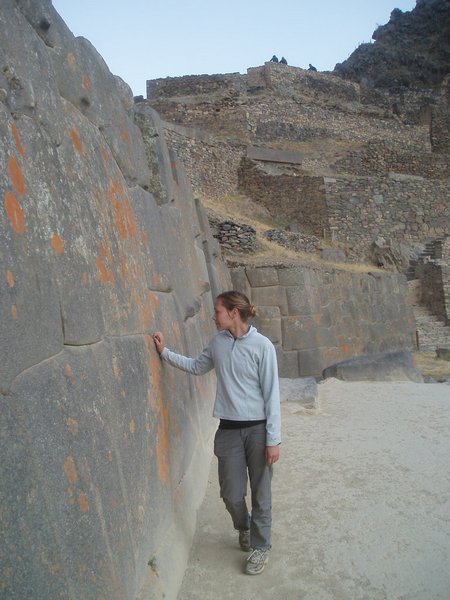

We caught a bus to Uribamba, then a second to the well-preserved, though over-touristed town of Ollantaytambo. As the mid-point on the Cusco-M.P. train line, a constant stream of tour buses has ravaged the ancient streets, and overpriced hotels and gift shops fill every corner. We had looked into the ticket and train prices for Macchu Picchu and had seriously considered giving it a pass, sticking to the cheaper and more accessible ruins that filled every inch of the Sacred Valley. But we feared reprisal from friends and family members, so like the endless hordes of tourists before us, we ignored the imposing mountain ruins flanking Tambo and made a b-line for the station.

Since every self-respecting adventurer had paid $400 for a 4-day trek on the 33km Inca Trail (Andie resisted my efforts to convince her to hike the whole thing by ourselves in one day), there were plenty of seats from Tambo to Aguas Calientes (the even more tourist-saturated town a few km from the legendary ruins). There were, however, zero seats available on the return trip; we didn't let this bother us too much and plopped down the $68 cash for our one-way tickets. We stocked up on snacks at the market (fearing the prices we would find down the tracks) and boarded the backpacker car for the 2-hour trip.

It was a rather scenic ride with good views of the raging Rio Uribamba, the Inca Trail and adjacent ruins, and the snow-peaked mountains to the north. As always, Andie slept through the whole thing, nullifying the "enjoyment of scenery" mitigation of the absurd ticket price.

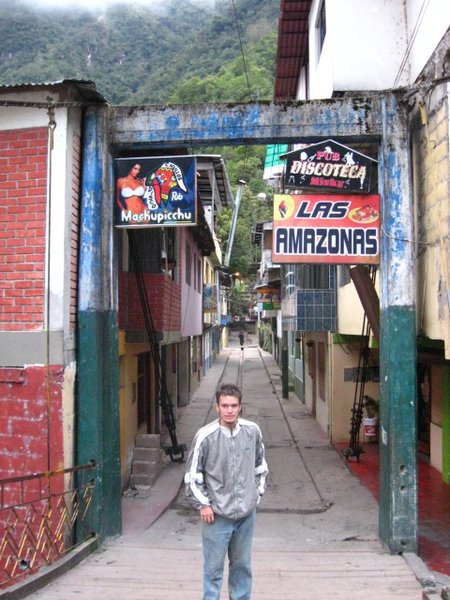

We had exactly 3.5 hours from the time train pulled into Aguas to the time the ruins closed for the day. When we arrived, it took us a good ten minutes to navigate through the maze-like craft market that emanated in all directions from the station. The town is divided by the river into a gringo and local side; the gringo side is entirely gringo-oriented restaurants, hotels, Thai massage parlors, and discotheques; 80% of the restaurants are billed as "pizzerias" and 100% offer 4 for 1 drink specials all day long. We found a somewhat jungly guesthouse on the local side, the price of which had tripled since its guidebook listing. After dropping off our stuff, we made a mad dash for the ticket booth where we discovered we would have to pay $60 in soles (not dollars or credit) and lost a few more precious minutes hunting down the only ATM in town.

Let me take a moment to berate a particularly nonsensical institution that has somehow taken hold in Europe and a handful of South American countries: the international student card. Somehow, a certain for-profit company was bestowed with the responsibility of issuing internationally recognized cards that would "prove" that a person was a student under the age of 26, and therefore eligible for all discounts. This card is obtained by calling a number, telling the person your age, and handing off your credit card info. There is never any effort made to verify your age or your student status; you just hand over the $25 and the card arrives in 8 to 10 business days. Once you receive the card, you must print out a picture of yourself from any inkjet printer and tape it onto the card - mine was a grainy, washed-out one from a recent snorkeling trip. I had purchased one of these and Andie had not; as a result I paid $20 less for my ticket than she did, even though she held an official Florida State University card proving that she began her studies there only a year prior. I don't know what system of kickbacks brought about this atrocity, but, for the moment at least, there seems to be little way around it.

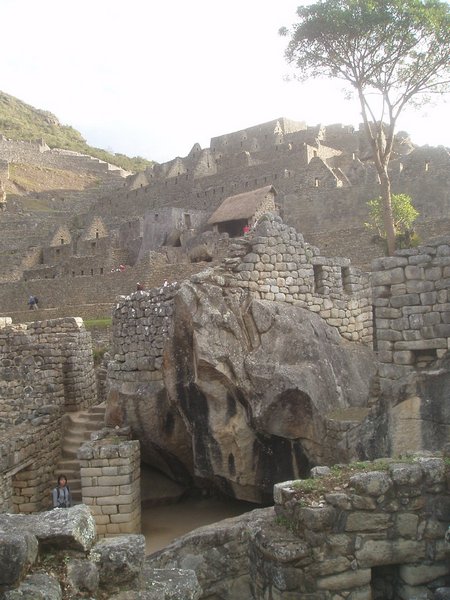

Once we had finally obtained our tickets, we jogged down a 2km road leading to the based of the mountain. The upward trail from there was not all that difficult but had the serious annoyance that it crossed the road about every 5 minutes, where there would inevitably be a ($14 roundtrip) shuttle passing by. Once we reached the entrance to the ruins, we were informed that the park would close in an hour and 15 minutes (a full hour earlier than we had expected), and our uber-expensive tickets could not be used for any subsequent days. So we set out exploring the lost city at a frantic pace.

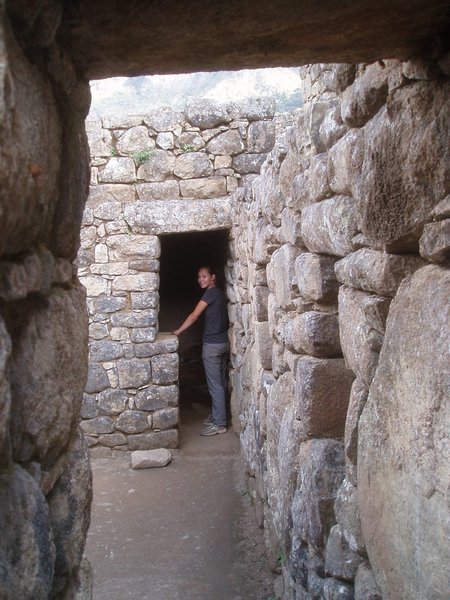

Neither of us had bothered to do the slightest bit of research on the place beforehand, so we really had no idea what to expect; from the wealth of pictures we had seen over the years, we anticipated that there was one photo-op, a bit of scurrying around the ruins, and that was it; in actuality, there's enough hiking options to keep you busy for a full day, if not more. With no map to guide us, we spent the first 15 minutes stumbling down trails that would get us nowhere fast; the first was a 90-minute trip to the Inca Drawbridge which sits towards the end of the Inca Trail, and the second was a 2-hour uphill slog to the top of Macchu Picchu mountain. Luckily we ran into some more knowledgeable tourists who set us straight and we were back to the main ruins with an hour to spare.

The third and most attractive side-trip can only be accessed prior to 1pm, and only if you're one of the first 400 people of the day; this is Wayna Picchu, the infamous mountain that looms in the background of every photo you've ever seen of the place. Though it looks like a serious mountaineering challenge, it is in fact easily hikeable in under an hour and a small collection of ruins sits at the top. We lamented that we had not planned for this, especially since there is a cave after a two-hour walk from the main site.

With time at a premium, our efforts would be focused on the central ruins. We snapped a hundred variations of the classic picture from every conceivable angle and followed the main circuit through the structures. Having never bothered to read the guidebook chapter on the place, I have no idea what we saw ruins-wise, but we did come upon two viscachas (rare Peruvian rabbit-squirrels), presumably waiting for hand-outs. Without making any real effort to chase anyone out, the guards started whistling at 4:45, but we continued exploring until we had seen every last inch of the main complex and left just before 5. A horde of buses sat at the ready just past the exit, but we followed the handful of people who descended by foot and arrived back in town shortly after dark.

The main street in the tourist district was similar to many other restaurant alleys throughout the world; a few representatives from each restaurant stopped us as we passed, showed us their menu (perfectly identical to ever other menu) and bombarded us with discounts and drink specials. The discounts got higher as we moved higher up the hill and, stopping at last at the final restaurant in the chain, we ended up sharing a 3-course meal of stuffed avocado, grilled trout, and a fruit salad for just over $3. While the price was high, the décor (alpaca-fur chairs), readable menu and elaborate presentation of the food justified the expense.

I have never been one to sew a maple leaf on my backpack or to deny my nationality (except in the case of touts who only ask to gauge the size of your bank account), but as we finished dinner, we witnessed an exchange that left me quite ashamed to be an American. A family at a nearby table received the quesadillas they had ordered, and the father was immediately struck with a look of extreme consternation, and loudly complained to the waitress that what they had received were not in fact quesadillas. Once the entire staff of the restaurant had assembled to hear his concern, he berated them, explaining that he had ordered the same in Lima, Arequipa, and Cusco, and had each time received a proper flat quesadilla, but what they had brought him tonight was rolled, far closer to an enchilada or burrito. Here was a true culinary adventurer; I resisted the urge to attempt to explain the subtle differences between the centuries-old civilizations of the Andes mountains and the second-generation Mexican immigrants that whipped up his beloved tortillas and cheese back in Boston.

Guinea pig castle

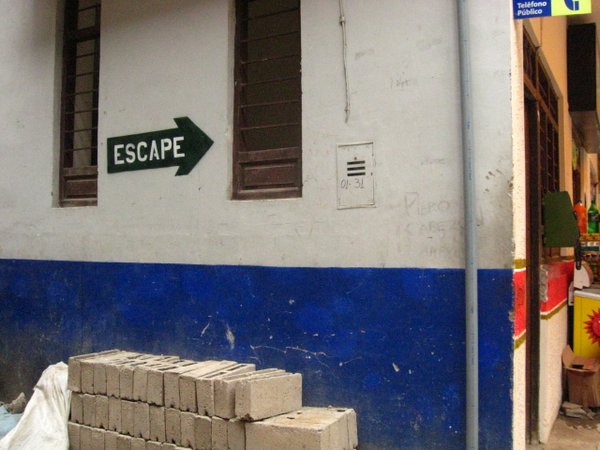

We saw these signs everywhere but never quite figured them out... fortunately, the need never arose...

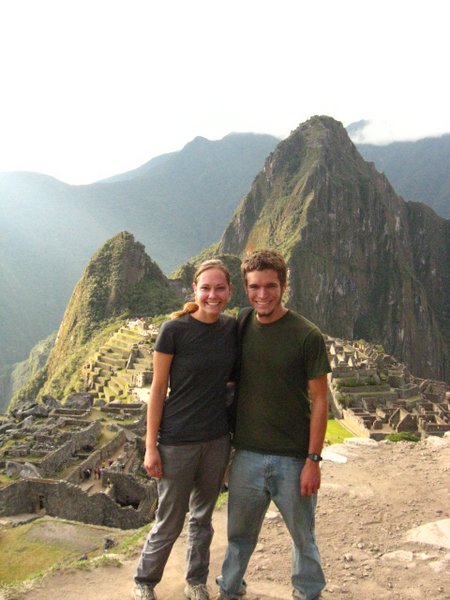

And now for a dozen more takes on the picture you've already seen a thousands times... I would suggest that you just hit up one of those carnival photo booths for this one - it'll be loads cheaper, and you won't have to spend 15 minutes chasing all the Asians out of the frame.

First viscacha sighting of the trip - they probably feed this guy.

Second viscacha in an hour.

One of Andie's many picture ideas that had the guards blowing their whistles at me.

Quite inadvertently, we sat at the American table...

After passing out at 8:30 the night before, we were up and ready at 6, but despite the 200 Wayna Picchu climbers who supposedly reached the gate at 7 each morning, the town was not an early riser. We went to the only open restaurant and ordered two breakfast dishes; without conferring with us, the restaurant owner decided she only felt like making one and eventually brought us a plate of Lomo Saltado and a cup of coffee. Since the Peruvian concept of a granola bar is a calorie-devoid rice cake with raisins, we grabbed a bag full of bread before heading out to the start (or end, depending on your perspective) of the "Inca Jungle Trail".

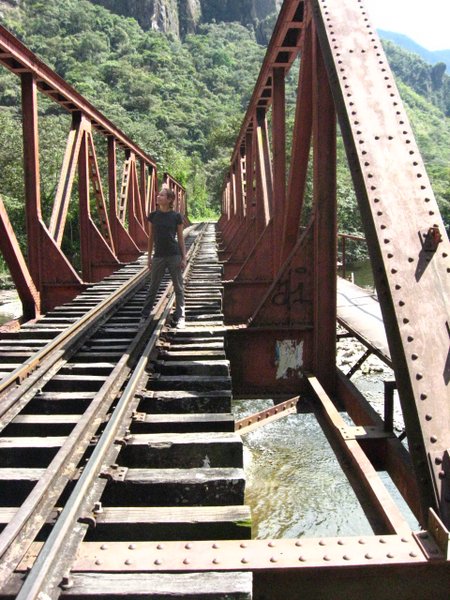

Crafted in recent years as an alternative to the expensive tourist train, this unofficial "trail" has exploded in popularity and inflicted upon the towns en route the same blight of backpackers that has forever transformed Aguas. The first leg of the route followed the train tracks for two hours to Hydroelectrica (a hydro-electric plant always referred to as if it were an actual town or the focus of a magical children's story). This is a fun route which makes you feel a bit like the tramps who plied the American rails a century ago. The raging Uribamba follows the whole length and flocks of hundreds of stunning green parrots squawk overhead. Trains are infrequent and loud, so although anyone you ask will finish their advice with the tireless warning "…and watch out for the trains!", it's not really a huge concern. The only real danger is a daredevil river crossing on an old railroad bridge that hangs some 30m above a pile of sharp, pointy, slightly moist rocks; while the engineers were kind enough to put a series of metal panels on one side, whether you use these or not will be wholly dependant on who you've chosen for travel partners and your susceptibility to peer pressure. When we arrived, a group of young tour participants had just finished crossing the span using only the tiers. Thinking ourselves to be true adventurers and far superior to a gang of teenagers who paid $400 to be spoon-fed a wilderness experience, we stepped out onto the tiers without hesitation. It only took a few steps over the void before we realized what a truly terrible idea this was, and we retreated (very slowly) to where we could safely move over to the walkway.

From the plant, it's possible to cross a bridge and hike for two hours through the jungle, and subsequently pull yourself across the stunningly deep canyon on a board suspended from a cable. Regrettably, we had neither the supplies nor the time to make this trip, so we caught a ride with a tour operator and zipped along the cliffs to the largely inaccessible town of Santa Theresa. When we arrived, the town's schoolchildren were staging a mock protest and we joined them in their march for a cleaner environment. Once we felt we had made our point, we set about finding a bus to Santa Maria.

At the station, we encountered a very peculiar situation; around 15 people were waiting for a bus to go to Santa Maria, and, at the same time, several bus drivers were sitting in their empty buses, presumably waiting to drive people somewhere, but somehow the two never converged. The whole town seemed quite determined to send all the gringos in an overpriced taxi, and, after 30 minutes of heated discussion, they succeeded in doing just that.

Had I understood the nature of the road we were to drive, I probably would have agreed to pay more than I did. The 35km one-lane gravel highway ran along one side of a canyon, inches from a precipitous drop of a thousand feet or more. Massive boulders and fragments of boulders clung precariously to the mountainsides, just waiting to drop on an unsuspecting motorist. It was, in a word, terrifying - especially given that the driver was flirting with the woman in the passenger seat the whole time - but thankfully we survived and reached Santa Maria without a scratch.

There wasn't much to this dusty little town, but it had the highest concentration of gringos of anywhere we'd stopped thus far. Besides the line of fruit sellers who were ready to sell their goods to any vehicle that might pass through, the only other inhabitants seemed to be a group of 15 Israelis and Europeans who had been waiting for the last 5 hours for a ride out of there. Fortunately, someone in our taxi spoke fluent Spanish and ascertained that we could buy "intermedio" tickets on a Cusco-bound bus that would roll through within the hour; this meant that we would spend the next 4-6 hours standing in the aisle as the bus roared up out of the jungle, over a 4300m pass, and back down to little Tambo. This plan worked splendidly (though perhaps not for the 15 gringos that the bus left behind) and, just after sunset, we arrived in the plaza we had left just 30 hours prior.

We tracked down a pleasant hostel that gave us a good price on a room directly across from the discotheque. There was no lock on the door, and presumably another guest could claim the third bed, but we solved both problems by jamming a chair up against the door.

A stroke of luck (or perhaps, sheer probability) put us in town for one of the area's many religious festivals. The organizers were handing out free pork chop and potato dinners in the market, and booze drifted through the crowds as locals and gringos alike danced the night away to the tunes of a live band. The children had been sent to the second floor and danced in a similar fashion while watching the action below through the drainage grates.

While I had previously suspected that I was immune to pick-pocketing given the atrocious state of my clothes (somehow the vile odor I acquired on my Panama trip had persisted through multiple washes), one extremely ballsy fellow gave it a shot. We were waiting for Andie's hot dog sandwich to be made at a small stand which sat directly across from a patrolman. Apparently, while we stood there and chatted, the would-be assailant snuck up behind me; but before I saw him, or the second cop that materialized from nowhere at just the right instant, the criminal was being forcefully hauled away, all the time exclaiming "I just wanted a sandwich." For all the bad press Peru gets for its criminal elements, they seem to have their tourists pretty well covered.

One of many gringo dining establishments in Aguas Calientes

You gotta love that shameless commercialism...

Walking down the tracks.

Luckily there was just enough space between the train and the cliff/wall to avoid being crushed

One of many flocks of wild parrots

Each pair of tiers on this bridge was separated by about half a meter of nothing, and that nothing was separated from the trickle of water below by about 100 feet...

Protest for a cleaner city.

Free food, booze, dancing, and live music - these Peruvians know how to celebrate a church holiday!

We were up at the crack of dawn and once again searching for breakfast; luckily this particular town had an abundance of Inca Trail porters, and the top floor of the market was full of men downing tasty rice dishes. We were only the second pair of gringos to arrive at the popular Tambo ruins; structure-wise, these are right up there with Pisaq and Macchu Picchu, but, since they're just a block off of the town center and require no steep, upward hike, lack the same sense of accomplishment.

We kept an eye on the town's second set of ruins all morning; these seemed to be in many ways equal to the first, but while the set across the valley was packed with tourists, archaeologists, and colorful local women with their llama charges, these were completely empty. We ascertained that getting to the ruins was a simple matter, and were soon edging along a steep cliff overlooking the structures. It occurred to us, though, that we were immediately visible from any point in the valley, and so too was it visible that there were only two of us on the path, a safe distance from any of the town's many patrols; this was enough to convince us to descend and settle back into the standard tourist mold.

A bus took us back to the transport hub of Uribamba, and another delivered us to the small mountain town of Chinchero, which managed to get itself placed (yes, the whole town) on the tourist ticket. This was most likely an economic stimulus move, as there was little to see or do in the place. We did catch the end of a wedding and joined in the crowd that piled several inches of confetti on the bride and groom's heads. After a cursory perusal of the town's small collection of ruins, we found a shared taxi to Cusco, which cost even less than a bus to the same place (apparently, all the money is in shipping the gringos out of the city), and we were soon back on the bustling streets of the capital of the Incas.

We had previously explored Cusco in the quiet hours of the morning and were not at all prepared for the vibrant city that awaited us. Having spent several days in tiny villages, the options for things to eat, see and do seemed utterly endless. We first visited the ruins of Qurikancha, where a Dominican church had been plopped down right on top of the old Incan stones. There were enough tourists here to justify hourly tours in everything from German to Japanese. By this time, we had about had our fill of ruins and soon left the town's top attraction to soak up the street scene.

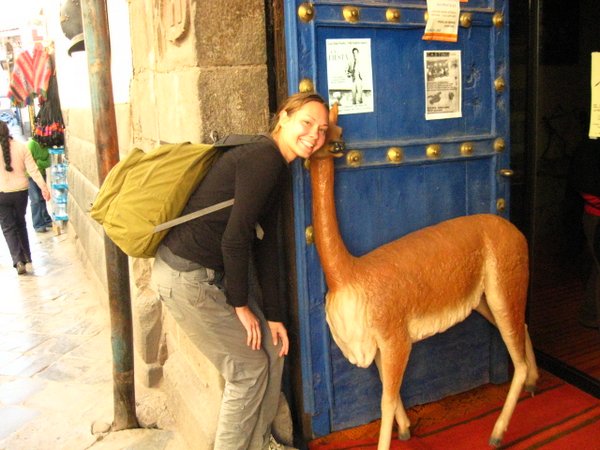

We found our favorite Cusco sight quite by accident. While strolling down a random alley in search of a cheap hotel, we noticed a wooden llama looking out from a doorway. Behind the llama, a contemporary art gallery, housing the works of Jesus Navaro, held exquisite sculptures made from animal bones. Each work contained over 7000 bones, from a swordfish's mouthpiece, to a guinea pig's ribs, and took him nearly a decade to complete. This was just one of many free art exhibits scattered throughout the city, all of which quite handily put the vast majority of western contemporary art to shame.

The night scene in Cusco seems as if it's been transported straight from a large European city. Scores of tourists and locals parade from plaza to plaza, troubadours appear and perform at random, and many a restaurant tries to draw the crowds through its warmly glowing doors. An Israeli on the Santa Maria bus had pointed us toward a street aimed at backpackers with rock-bottom prices; we had some trouble finding it initially, but once we turned a corner and had three separate offers for weed within five seconds, we knew we had reached the right place. Unfortunately, we were a bit too eager and settled for perfectly normal dishes like Alpaca steak and vegetable curry, only to discover that just around the corner sat the holy grail of menus: a three-course meal including a salad, drink, pancake, and guinea pig big enough for 2 for only $5 - the crafty rodent had evaded us once again.

Ollantaytambo ruins before the gringos wake up.

Sun-baked adobe

Puppies

Andie and a local

Main plaza of Chinchero

Wedding party

Andie and the Vicuna

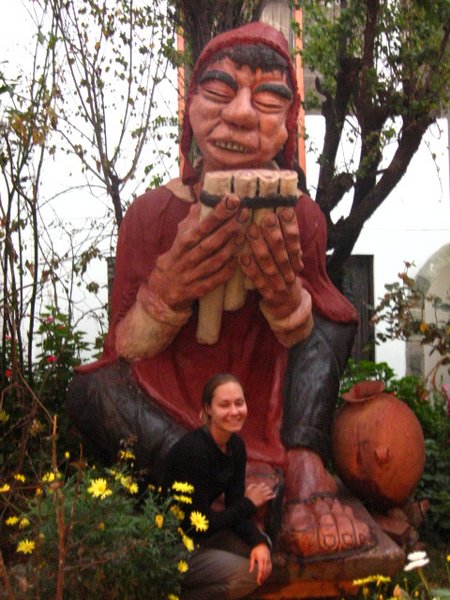

One of the taller pan flutists in Cuzco

The oven where our guinea pig would've been prepared, had we thought to order it...

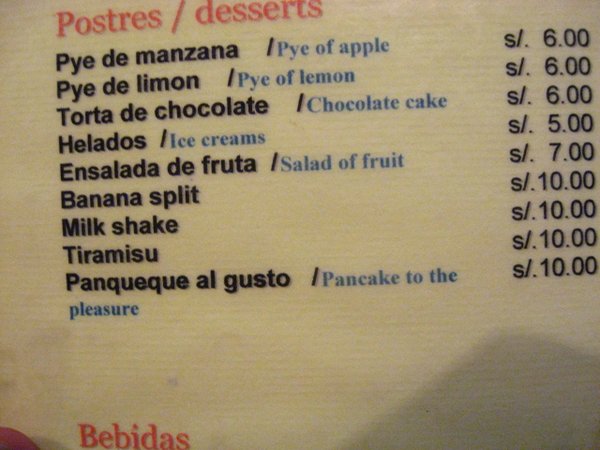

Peruvian menu translations aren't of the same caliber as their Asian relatives, but there are still a few good head-scratchers...

We caught an early morning Mass in the city's second largest church. There were around 20 people in attendance and the aged priest was running the whole show by himself. His Spanish was mostly indecipherable and was not helped by the fact that he delivered his lengthy homily while staring at his feet.

As we set out to leave town, we encountered a huge military/political ceremony complete with rifle salutes and a parade featuring kids dressed in all sorts of crazy, traditional dress. Naturally we had no idea what it was all about and quickly lost interest.

The moment we entered the bus station, we heard around 5 distinct touts cry out "Puno Puno Puno" from various corners of the room. The first lady we spoke to wanted 30 soles, so we walked over to another who quoted us 25; these two then got in to a bidding war and within 7 seconds, the price was down to 10. Neither of their companies actually offered seats for 10, so they directed us to a third company which reluctantly sold us the $3 tickets for a seven-hour ride.

The bus went the whole way without a single food break, so everything had to be obtained by dealing with the women who ran up and shouted through the open windows at every stop. The problem was that I had no change, and was not about to toss a 10 sole note out the window for a 1 sole purchase; I trusted these people to an extent, but trusting that they would go to the trouble of standing on their tip-toes to feed exact change back through the window, when they could simply walk away with ten times the normal profit, did not fall within my range. At one point a woman and her son came onboard and set up a mobile restaurant in the aisle; they served up chunks of pig, sauce, and a drink to whoever was willing to pay the premium - I managed to negotiate a pair of warm, pig-flavored potatoes for a reasonable price.

Arriving in Puno, we sadistically ordered a bicycle rickshaw driver to peddle us the 3km uphill to the town center. Needless to say, he spent the majority of the trip trying to sell us on hotels on the periphery which would allow him to stop a bit earlier. It may have been wise to take his advice, as all the hotels in the guidebook had upped their prices dramatically; we tracked down a place called "Hospedaje Jesus" which appeared to offer both nightly and hourly rates and had the soundtrack to match, but was otherwise quite an acceptable place.

On the main pedestrian walkway, we found that many of the restaurants claimed to cook guinea pig and we eventually settled into a semi-fancy one with a live music and dance performance. To our dismay, this particular restaurant only gave us the head and limbs, and left out the meaty midsection of the rodent, so the portions ended up being roughly equivalent to 4 small chicken wings. As for what restaurants such as this do with the body of the cuys - perhaps you had better think twice before you order your pizza with "the works".

A random parade in Cuzco

Bus station snacks.

Random drummers in the streets of Puno.

Free restaurant dance performance.

All that remained of our fried guinea pig.

Andie the savage.

Scary.

Only one travel agent was open when we had finally picked the cuy bones from our teeth and set about looking for a way to get out to the islands of Lake Titicaca. Having arranged the trip the night before, we arrived at 7:30am to set out on our two-day tour, and fifteen minutes later, a bus full of gringos picked us up and drove out to the boat dock. Here, literally hundreds of westerners piled on to dozens of identical boats. While we waited for five other boats to move out of our way, a pan flute and ukulele player boarded our boat and played a sequence of three 2-minute song clips, then proceeded to go to each passenger to ask for a tip. We subsequently heard him play the same brief melodies on a number of neighboring boats. These musicians have become commonplace on buses and boats throughout Peru, most likely because virtually everyone onboard gives them money. Sure, the first time you hear something like this, it's folksy and charming, but it gets old fast - if you ever encounter someone like this, don't give him anything; I can still board most of the world's transport vessels without being subject to a shrill musical interlude and inescapable begging, and I'd much prefer to keep it that way.

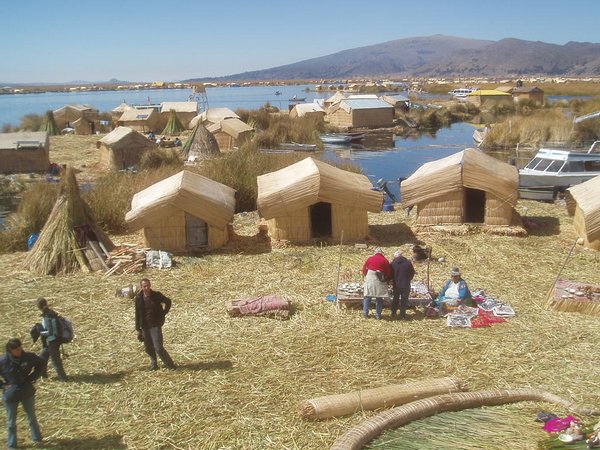

Once we had finally coaxed our way out into open water, it was only a 30-minute ride until we arrived at our first port on the Islas Uros. These are a chain of 70 man-made floating islands with over 3000 inhabitants. The islands themselves, the structures on them, and the boats that ply the water between them are all constructed from a reed that grows in the shallow waters of the lake. This magical plant is also edible and flammable, and thus provides for nearly everything the islanders could need on their centuries-old, self-imposed exile; nowadays, it's not uncommon for them to get a hankering for a cheeseburger or a bottle of Inca Cola (or anything that's not a flavorless reed), and so they frequently put in orders with the boats out of Puno.

The locals put on a thorough demonstration on how to build such an island, and we were immediately anxious to go home and give it a shot. We also got lessons on how to eat the reed, cook fry bread, and domesticate a fishing bird. Most of the gringos on our tour paid a few extra bucks to take a ride in a reed boat to a neighboring island; the inhabitants of the originating island executed a fascinating song and dance routine to see them off, which included such inspired lyrics as "Gringo, gringo go so far… how I wonder what you are". Andie and I, along with a few other thrifty backpackers took the motorboat across some minutes later and arrived long before the row-powered craft.

What followed was an excruciatingly slow three-hour trip to Amantani Island. Whether it's to save gas or respect the local ecology, all of the powerboats on the lake move about as quickly as a paddleboat, so a distance that would have taken 20 minutes in a Panamanian jetboat, took us well into the afternoon. The engineers of the vessel had found a way to pull all the fumes from the engine into the cabin, so I passed most of the trip on the roof, my shirt wrapped around my head to guard against the frigid temperatures of the 3800m-high lake.

At Amantani we were divided up and sent to our host families. Unfortunately, Andie and I were sent off by ourselves, without the aid of one of the Spanish-speaking gringos (whether its due to being European or simple trip duration, virtually everyone we met in Peru seemed fluent in the language). It may not have made much difference as the old woman who hosted us didn't seem to speak much Spanish either; all of her sentences were just a long string of "paras" alternated with other simple Spanish words; as an example, to indicate that she would lead us somewhere, she would say something along the lines of "para Marta para accompaner para ir para…". The result was that we rarely had any idea what we were expected to do at any given time.

We watched our host cook for a full 90 minutes before we finally got our lunch of quinoa soup and multicolored potatoes around 3:30. Then, while we were still sitting in her kitchen, she tried to sell us some of her handicrafts at inflated prices; this is just one of the rather awkward methods used by the islanders to extract additional funds from the rich westerners. Following this, we had a slow hike up the hill to the court where the other gringos were playing soccer. We had a number of slow hikes around the island as our aging host moved with all the alacrity of a three-legged turtle, and the chain-smoking Europeans in our group moved slower still.

Even more important than the sale of weaved goods, is the complicated gifts system. Our guidebook recommended that we bring fresh fruit for our hosts, but this simple gesture has since mutated into an underhanded process of repeated suggestion, extortion and kickbacks. The con goes as follows: over lunch, your host finds occasion to mention several things she needs around the house, in our case it was candles and batteries; on your post-lunch hike, you happen to pass by a number of shops that sell not only sodas and candies, but also whatever goods might be on your host's shopping list; the shops charge approximately five times the going rate for these items and the profits trickle back down. On our departure, we presented our host with the fresh oranges we had carried all the way from the mainland for her benefit, but without so much as a "para gracias para", she tossed them aside exclaiming "un regalo poquito!" Nothing changes a people like a bit of mass tourism.

Our boat's guide led us on a hike up the mountain to where we could see the two ceremonial sites Pachamama and Pachapapa. All the islanders are officially Catholic and attend church every Sunday, but still find time to make an annual pilgrimage to the shrines of the earth mother and father. From a tourist's standpoint, these shrines are little more than fenced holes in the ground, but the view from the mountaintops, which takes in the seemingly endless expanse of water and the distant mountains of Bolivia, is worth the hike.

Coming back down after sunset was a bit of a trick, but luckily someone met us at the court to direct us through the dark fields to our house; there had apparently been considerable trouble with losing gringos in the past, and each family made absolutely sure that you could tell someone their address (ours was Marta #5). The evening meal was soup, rice, and some sort of potato stew; the islanders had all become vegetarian so as not to have to figure out the bizarre dietary restrictions of their guests. Next, our host dressed us up in traditional Andean costume - Andie wore three layers of skirts, a couple of blouses, a belt, and a cloak, and I had a poncho. Dressed thusly, we were escorted to a bonfire where all the gringos were dancing to traditional tunes (actually one traditional tune played over and over again - for a tip, of course). We bowed out after the third hold-hands-and-run-in-a-circle dance, and passed out around 10.

A touch of Venice in Lake Titicaca.

Surfing through the Totara reeds

Pet bird and tourist

Not only good for building islands, it's tasty too!

The same reed that makes up the islands can also be set aflame for cooking... does this seem potentially problematic to anyone else?

They couldn't get cats to live on floating islands, so they had to improvise...

How to build an island.

So long gringos...

The farewell dance

Peru has over 6000 varities of potato - choose six and add a hunk of cheese and you have yourself a meal

Sunset over the ruins

Dressed for the ball

Para Andie para Marta

We were awoken at around 6 by the old man banging on our door (he had previously not spoken a word to us - most likely because his Spanish vocabulary was about 5 words in total). He had brought us a guestbook to sign; once we did, he insisted that I give him my pen as a gift. I fervently insisted that it was my only pen and I couldn't part with it, but he just stood there repeating that it should be a gift to him. So I handed it over and he thankfully left without stealing anything else from my meager possessions. Fortunately, I did have one spare pen which I would keep well out of sight for the rest of my time on the island. A random guy from down the street soon dropped by with a bucket of hot water which we gathered we were supposed to use to bathe, but there was little chance of either of us getting wet on the brisk, 40 degree morning.

After a pancake breakfast, we were led back to the waterfront, and soon began our one-hour ride to Isla Taquile. Here, we took a 40-minute walk to the town center and visited a communal weaver's market, which justified its exorbitant prices with a plaque proving that UNESCO had declared them the best weavers in the world. After a free period, our guide took us up out of town to a section of the island where 20 different restaurants were set up to handle the multitude of tour groups that visited daily; without mentioning a price, they had us all sit down for a meal. Naturally I extracted a price, which turned out to be 5 times that of a comparable meal in town. We were too far from the plaza with too little time, so we went to each of the tour group restaurants to see if any of them would negotiate; all served the same exact meal (trout, french fries, and rice) and did so at the exact same price, but we eventually found one willing to drop the rate by half. We made it back to the boat at the same time as our group and embarked on the three-hour ride back to Puno.

Back in town, we sought out the Hare Krishna restaurant for dinner. At the beginning of our trip, we had been treated to one excellent dish after another, but in recent days, the food had devolved into exceedingly greasy fare with french fries accompanying absolutely everything (even if there was already rice or potatoes), so we were more than ready for a reprieve. The restaurant had the usual smattering of Krishna posters, but there were no pink-robed devotees to be found, and besides a tasty chunk of fake meat, the meal was straight-forward, run-of-the-mill Peruvian cuisine.

Local children examining their bounty of colored pencils from the latest wave of tourists.

Sith lord or indigenous woman - one of the two.

A giant tufted chicken

Herbal tea

Isla Taquile

Third-world zoos generally have a bad reputation as far as habitats go, but this one takes the cake.

We followed the guidebook's terrible directions to the bus station and only found it after several course corrections. There, we bought another pair of $3 tickets for the 6-hour bus ride to Arequipa. Most of the scenery followed the same desert/mountain motif that covers all of highland Peru, but we did pass by a couple of salt lakes complete with flamingos, and several herds of vicunas (the wild equivalent of llamas). Arriving on the outskirts of the city, we used the excellent taxi dispatch system (they have a list of destinations and the prices they cost, and the drivers actually follow them!) to travel the 3km into town for a buck.

Traffic in Arequipa is quite terrifying as none of the intersections have any kind of light or sign that anyone pays any attention to, so all the cars just drive through the intersection at breakneck speed and slam on their brakes whenever they encounter another car that's doing the same thing at the same time - this happens approximately once every block.

This is the wealthiest city in Peru and much more Spanish than anywhere we'd been so far. Stunning colonial structures line most of the streets, the churches are exceedingly ornate on the insides and out, and the dining options are as varied as a medium-sized European city. Random musicians play in the plazas and men on stilts and in SpiderMan costumes hand balloons to children and advertise cell phones. Radio Shack is here, as are plenty of high-end chocolate shops, but delicious street food and $1 4-course meals seem to be keeping American fast food at bay for the time being.

After some searching, we found a room for a rather pricey $13 in an old colonial building with a pleasant courtyard; the only other occupants were 3 Americans in some distant corner of the motel, so we had 4 beds in a massive room all to ourselves. We wandered around town, sampling the many culinary treats; these included cheese ice cream, tamales with raisins, and giant corn on the cob with cheese. We found a Moroccan restaurant that for $5 served up menus which were comparable to the typical $30 selection in the States. Sadly, the chef was delayed, so we instead went to Bhopal Vegetarian Restaurant, which had Krishna on the menu cover, but once again bore no relation to the sect. We got a delicious paella dish with soy chicken, along with soup, fruit salad and tea, for $2.

As part of the city's weeklong founding celebration, the municipal theatre was presenting a free performance called "Cantemos, Bailemos"; strangely, this show contained no dancing, and even the singing disappeared after the first act.

Bike taxi

Baby in a crate

Rickshaw race

Fruit market

Llama crossing

Vicuna herd

Once a monastery, now a mall.

Ice cheese!

Grand architecture of Arequipa

Biker girl manicans

Spiderman

We caught another no-hassle $1 taxi to the station around 7 and got on a bus bound for Chivay at the head of the legendary Colca Canyon. This was a remarkably unpleasant ride, since a standee, who smelled remarkably like rotting fish, decided to sit on Andie for most of the trip. The movie was a 3-hour gore-fest about an evil mist and a horde of generally disagreeable people it held captive in a supermarket. We backtracked for the first two hours on the route we had followed into town, but the last hour was new and crossed a high mountain pass complete with plenty of icicles and vicunas.

Once in Chivay, we made several circuits of the markets and bought lots of cookies, cocoa puffs, and ice cream. We ate lunch at a place with an 85 cent menu - the first two courses were decent, but the dessert was almost certainly dish soap, and the drink was a diluted form of the same soap.

We decided to follow a trek recommended by the guidebook and crossed the canyon (not particularly deep in these parts) to follow the mostly deserted road on the south side. At the next town up, we got directions to a nearby collection of pre-Incan tombs, and after getting seriously lost, bushwhacked up the terraces to where we found the well-established trail. A series of small ruins beneath a rock overhang contained well-preserved skulls (some trepanned), other bones, and even some remnants of mummified remains.

On the way to the ruins we encountered a particularly insidious plot by some of the locals. A small girl had dressed herself, her baby brother, and her pet baby alpaca in traditional clothes; she had assembled a collection of traditional foods and herbs in an informative display. The object was to appear so cute that any tourist would have no choice but to take a picture, no matter the price. We were thusly enticed, but upon offering her 15 cents (the cost of an ice cream cone or 3 loaves of bread) for the privilege, she immediately became much more business-like than her demeanor would suggest and demanded a larger sum - needless to say we don't have any photos of the world's cutest Peruvian baby/alpaca combo.

We hiked another hour to a bridge across the canyon; here, fighting off bouts of vertigo, we looked down to see many more tombs precariously perched on the cliffs far below. Later, overlooking the bridge, we saw a herd of donkeys and sheep make their way across; the baby donkey was understandably freaked out. We grabbed a colectivo back to Chivay and found a hotel with private bath for what half what we had paid for one with a bano compartido in Arequipa. We got dinner at the place next door to where we had eaten lunch; once again, the meals were nearly edible, but the after-dinner tea was a heated version of the same dish soap we had had in drink and dessert form earlier. The market was still pumping on all cylinders and we stumbled upon something we never expected - a cart of around 10 whole skinned alpacas - I suppose all those restaurant dishes must come from somewhere.

Lounging piglets

Pre-Incan skulls

Bridge over the canyon

Cliff-clinging tombs.

Terrified livestock

Cart of skinned alpacas

Friday would be the start of the longest bus ride of our lives thus far, and it wouldn't begin until after an initial 4-hour bus ride. We got up early to make the most of our freedom before our 9am departure. Open market stalls were hard to come by, but we did manage to find a pair of the town's signature tire shoes; compared to the average Peruvian, it seems I have enormous feet, but the shop-keeper was able to find one XXL pair at the bottom of the pile - he tacked on an extra 30 cents for the excess rubber required.

We chose a different bus company than the one we'd used to get there, and I was immediately pleased with my decision as I watched both a goat and a llama board the bus on which we had rolled into town. The movie was much better this time around - as usual, it was completely in Spanish, but as is the case with most of his movies, Quentin Tarantino's Desperado transcends dialogue.

At the Arequipa station, we raced in the direction of the loudest "Lima Lima Lima" cries and bought $10 tickets for the 18-hour ride to the capital. Perhaps the price tag should have told us something was amiss, but the promise of "semi-bed seats" by the company representatives temporarily quelled our fears. Our bus didn't show up until 10 minutes after its scheduled departure time, and then we had to wait for a company official to carry out a bizarre ritual of video-taping each of the passengers. The term "semi-bed" only meant that the seats reclined to about 10 degrees from the vertical (at least this was the case with our seats - those in front of us lowered to our laps). The movie selection included a rather obscure Samuel L. flick and a Kung Fu show entitled "The Postman Fights Back". As a caver and die-hard economy traveler, I never thought it possible that I'd be a victim of claustrophobia, but after about 10 hours with only 6 inches of breathing room, I came dangerously close to flipping out; luckily this subsided with sufficient sleep deprivation.

Something very strange about the Peruvians, given their generally cool climate, is their complete intolerance for cold or even reasonably warm temperatures. The "AC buses" were uniformly heated to around 80 degrees, enough to make the two of us uncomfortably warm in our short-sleeved shirts, but still all the other passengers wore jackets, sweaters, or scarves. On our last, interminably long bus ride, I found myself pressing as much of my body as possible up against the freezing window, trying to leech off just enough of the cool to keep myself sane.

Signature handicraft of the city: sandals made from recycled tires!

Every playground needs a VW bus!

Baby alpaca lost at the bus station

Boarding the buss

Desolate...

The dunes of Peru

After our visit to the YoguMisti plant!

One of many bone sculptures.

We arrived in Lima around 6:30 in the morning, a full 2 hours before anything in the city opened for business. The available street food seemed to be limited to yam sandwiches and hot quinoa drink, neither of which really met our criteria for breakfast. We took a bus to the expat-heavy Miraflores suburb, where an abundance of wealth has coated the desert cliffs in thick ivy, and provided miles of ideal seaside jogging paths. We soon found it was impossible to find an English or American breakfast for even as low a price as it would cost in either of those countries.

Returning to downtown, we grabbed an excellent hamburger and trout lunch from a small café and strolled around town, seeking out museums and churches, and sampling such delicacies as hard-boiled quail eggs and coconut chips. For a town of 8 million people, Lima doesn't feel that huge, but does have many big city accoutrements - one particularly unique sight were the groups of street performers who would run into a crosswalk during a red light, juggle or do cartwheels, and then collect tips from the waiting drivers. There was also a number of battle tanks scattered around town. The only memorable official attraction of the day was a set of catacombs where the monks had arranged the skulls and femurs into concentric circles.

For dinner, we found the typical restaurant alley and got set menus which included ceviche (raw fish cooked with lime) and free pisco sours. Menus throughout the country invariably feature a free dose of the national drink, but, never one to intentionally inflict pain on myself, I had always declined it. Here they had brought two glasses automatically and I got to experience a sensation akin to a liquid Warhead (obscure reference to sour candy from the 80s).

Taking the fastest straight-line path to the airport bus stop, we passed through a somewhat sketchier area. While buying some water in a shop, a tout approached us and asked us where we were from. I replied "Zimbabwe" and without hesitating for a moment, he responded "Ah, Zimbabwe - en Africa del Sur, verdad?", I said that this was correct, and he naturally followed up with an offer to sell us weed. I left this encounter with a new appreciation for the geographical knowledge of the Peruvian pusher; I had no idea Zimbabwe was even a cognate.

We took a circuitous bus route that stretched the 7km trip between us and the airport into a 90 minute ride. Security confiscated our water, and with no drinking fountains in the terminal, we passed the next 8 hours before Ft. Lauderdale without a drop. Sometimes I suspect the new liquids regulation has less to do with combating terrorism than it does with boosting sales of the airport's $3 water bottles (not to mention the travel-size toiletry industry). Back in Orlando, we took a spacious, air-conditioned city bus back to Piet's house and returned up the turnpike to Gainesville.

Miraflores: practically the only greenery within a thousand miles - it's amazing what you can do with a bit of money and hundreds of irrigation lines...

The Huaca pyramid of Miraflores which has recently started charging admission (this shot was taken through the fence bars).

Red light gymnastics

One of several somewhat threatening military vehicles around town.

Andie seemed to have a morbid fascination with the butcher stalls...

101 grains and dried fruits.

Food: Very tasty and somewhat varied - meals usually include soup, a rice and meat dish, and a herbal tea (often made with real herbs). Breakfast is not particularly breakfast-like.

Scenery: Mostly one big barren desert (for the coast and highland regions), but lots of big mountains and ruins everywhere.

People: Very friendly and helpful. No English spoken. Taxis and tuk-tuks typically not obnoxious and touts infrequent. Attitudes toward litter much better than in most places.

Weather: Perfect in the winter - blue skies and cool temperatures every day, and never a drop of rain. Sun block critical - you will burn in about 5 minutes unprotected (less if you're not tan). No mosquitos or other bugs (that we saw).

Time required: Assuming you don't fly everywhere, you need a lot. It takes 24-30 hours on a bus to get to Cusco. We moved fast for 2 weeks and only saw the southern Gringo loop. Airfares are cheap for Peruvians, but about $800 roundtrip for Americans.

Dangerous? Sure didn't seem that way, though we avoided going to remote sights by ourselves due to the many warnings in our books.

Overall: Probably one of the best destinations in the Americas. Definitely way more interesting than Costa Rica or Panama.