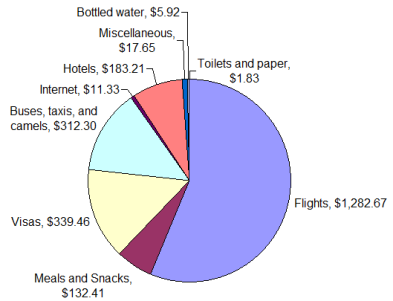

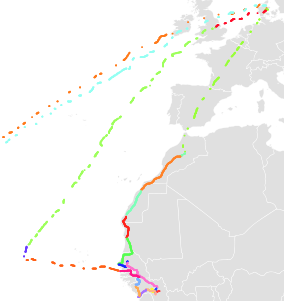

Return to West Africa, December 12th, 2013 - January 10th, 2014

FLL -> Copenhagen -> Marrakech -> Imlil -> Western Sahara -> Mauritania -> Dakar -> Touba -> Dalaba, Guinea -> Sierra Leone

-> Conakry -> Gambia -> Cape Verde (Santiago) -> Sal -> Manchester -> Copenhagen -> FLL

Mamou Junction

Attendez. This meant 'Wait'. It was the first thing I had been able to pick out from the collection of responses I had drawn out of the driver over the past four hours. He was an amiable enough fellow. He answered all of my questions with a broad, understanding smile - even the third or fourth time I asked them. A second car left for Kissidougou - this was on the same road as Faranah - only three hours further. Couldn't they just take me that far and find someone to fill my seat for the next leg? Did I know enough French to propose this?

Leafing through the pages of the guidebook, I began to piece together what it was going to take to get to Kabala, and then onward to an international airport. Communal taxis. A lot of them. With two in the passenger seat and four in the back. Some legs of the journey would only have one car a day.

The junction heading to the border was just before Faranah. If we left now, we would reach there at dusk. Then I would be left to hitchhike, or just hike, the last twenty miles to the border, and the fifty beyond that. Very few vehicles plied this particular route. Fewer picked up hitchhikers in the middle of the night.

My wallet had a sickly thinness to it. The largest bill in Guinean currency is the 10,000 franc note, which is roughly $1.50. Five days ago, my wallet wouldn't close around its formidable sixty dollar stack. Now I had 3000 francs. I could buy 18 mini muffins, or 6 bags of peanuts, or I might be able to negotiate a plate of rice and palm oil. There were no international ATMs in Sierra Leone. Once I reached Kabala, I could likely convince a volunteer to exchange paper leones for electronic dollars. Would there be volunteers in Kabala? We had made plans for the mountaintop New Years party four months prior. Maybe they had since opted to hit the beach instead?

Was I really going to spend the next three months hiking through unfamiliar jungles, on paths that had not been documented in the past 70 years, connecting villages that may or may not still exist? Would this actually work? In Dalaba, the sun had been relentless, and shade hard to come by. Perhaps Salone wouldn't be as deforested? I had returned to the hotel each afternoon exhausted; my plan was to hike thirty or forty miles a day, but in Guinea, fifteen miles over the course of a few hours had sapped away every last ounce of strength. Perhaps three meals a day of white bread and oil were not enough to keep me going?

And what about the part where I introduced myself to the chief and slept in a new village each night? Did I really want to spend the last four hours of every evening awkwardly conversing, or pantomiming, with villagers who shared little in the way of background or language or interests? I still hadn't picked up a mosquito net; would I find myself in straw huts rife with malarial mosquitos and Chargas-loaded kissing bugs?

Then I thought of Christmas - of the smell of the tree, of turkey and stuffing and sweet potato casserole. I thought of friends and family gathered before a roaring fire, sipping hot apple cider and egg nog. One small boy had wished me a "Joyeaux Noel" - aside from that, it was just another day. Would New Years be the same? I had just gotten an invite for a party on the 1st back in Gainesville. There would be homemade pie.

My mind flipped back to the gare routiere. Touts for Conakry were pulling people from every corner of the lot. Every ten minutes, another packed car would take off, a towering pile of rice bags and chickens lurching to and fro with each turn. Each car had at least two chickens hanging by their feet, clearly puzzled by their lot in life. Conakry, perhaps devoid of a thriving poultry industry, did have an airport. And I even had a valid visa for Guinea. My cancelled Peace Corps passport, with its shiny 3-year visa, would likely work well enough at the land crossings, but it would take more than a few 5,000 leone notes to get past the computers and biometric scanners of Freetown-Lungi International. From Conakry, there was a flight each night to Casablanca; I could be in New York by the 30th. In a mere 24 hours, I could find myself 5000 miles from this accursed continent and its tortuous transport. In 10 hours, I could have a seat to myself and legroom and air not tainted by the stench of burning oil, or gas fumes, or clutch smoke. Sure, a $1000 flight was a bit on the steep side - quadruple what I had paid for my first jump across the pond - but to be magically transported in one night over a distance more than double that which I had covered the past two weeks, through innumerable nights of untold suffering - it was but a pittance.

I retrieved my 60,000 francs from the driver and carried them to the first car in the queue. 63,000 was the price. It seemed I wouldn't be picking up any mini-muffins for the 6-hour ride. The car pulled out of the lot and my aspirations for Salone turned to a blur in the rear view mirror. The road map, the homemade gazetteer, the extra passport, the contact list, the cell phone and charger - they were all just dead weight now. Was this really the right decision? After months of planning and preparation and justification to friends and family? I was a mere thirty miles from the border; OpenStreetMap showed nothing in the way of trails or settlements, but it was likely just a matter of following my compass south. It was too late. That opportunity had passed. Perhaps I would try again in a year. Perhaps I would buy a motorbike.

Florida to Scandinavia for $99, House Salad for $22

My Peace Corps journey had ended a little sooner than I'd expected. My plans to document the country's multitude of beautiful trails and rocks and caves remained largely unrealized. My promises to visit each of the other volunteer's site by bicycle or foot, from my distant mountain outpost in the diamond lands of the east, increasingly seemed as if they would never be fulfilled.

But I still had my Peace Corps passport with a 3-year Sierra Leone visa. Sure, the director had said it would be cancelled the moment I got home, but the land borders had no computers - there was little chance they would check up on it - and even if they did, such things were easily remedied with a few thousand leones. And I still had my phone and a list of numbers and addresses for all the volunteers in-country. There was no reason I couldn't just go back and do what I would've done anyway - only without any pay or medical support. Yes, I had begun to resume my life in Gainesville - I had leased a room and bought a school bus and taken on various projects, and yes, my family would be expecting me home for the holidays. But was I being true to myself and my spirit of minimalism and spontaneity if I couldn't just throw it all away, fly across a few continents, and do something completely different?

The flights to Conakry and Monrovia never got much under $1200 roundtrip, and besides, there was no way to say when I might return. I resolved to get to Morocco from Europe and work my way down the continent by any means I could find. There was a map floating around Facebook that projected most of the larger countries in the world inside the bounds of Africa. I would be going roughly the length of the US. But I had done this plenty of times - sometimes in as little as two days - I wasn't intimidated.

Edwin had discovered an airline called Norwegian that flew to Scandinavia from Florida, New York, and LA for under $200 each way, and he was flying out to visit his girlfriend in Copenhagen for the month of December. I went ahead and booked his outgoing flight, along with another into Marrakech. At the time, getting across the pond for $184 seemed like the best thing ever, but then two weeks later the tickets dropped to $99. Brett led a weekend trip to Copenhagen to hammer home the ludicrousness of it all. I had less luck finding reasonably priced return tickets, but, at least for the time being, this was immaterial.

My efforts to scrounge up one or more travel companions were largely unsuccessful. Few were thrilled with the prospect of spending Christmas in a remote African village, five thousand miles from home and relatives and holiday cheer, and burning through a small fortune in the process. I did find someone to share my drive up to NC where I would leave my car and stuff; she was going to visit a Danish friend. We also discovered that Dayna was flying to and returning from Copenhagen on the exact same flights as Edwin to visit her Danish boyfriend. This seemed a peculiar reoccurring theme.

Jets in the Norwegian fleet are futuristic and spacious, and have plenty of movies and games on offer, but if you want anything in the way of food or drink on your nine-hour flight, you have to shell out $80 extra. They make a point of flanking every American with groups of rich Scandinavians, so that it's a given that everyone around you will have ordered the meal plan, and after the third or fourth round of delicious hot food and juices and coffee, those $9 sandwiches on the e-menu are starting to look practically justifiable. We arrived in Copenhagen at noon. My next flight was at six the following morning. This left us fifteen hours to party with Edwin's glut of Danish friends before I had to catch a night train back to the airport.

One by one my credit cards were rejected at the train ticket counter, and the ATMs were no more receptive. Edwin had only a few kroner and little to spare. I would have to walk the five miles into town. This gave me the chance to explore a bunch of boring commercial districts, as well as Freetown Christiania. This is a giant commune that considers itself separate from the EU - a status which entitles them to openly sell and smoke pot. Copenhagen's downtown was ramping up for the holidays and had a slew of quaint Christmas villages selling waffles and roasted almonds. A large tent in one of the squares advertised free meals for the homeless; this was tempting, since even a plain waffle ran about $9.

As the temperatures hovered just above freezing and a light mist slowly saturated my clothes, the hoodie and jacket I had packed were slowly losing the battle to ward off hypothermia. I started on the hike to see the mermaid and then thought better of it and set out to find Edwin instead. Reaching a square encircled by coffee shops, I used my smartphone to tap into unsecured wifi, and conveniently, Edwin did the same at roughly the same moment about two-hundred feet away from me. This was serendipitous, since we had never agreed on a meetup time or place and had each covered many miles since we had last spoken five hours before.

We explained to Edwin's friends that we are on a tight budget and they took us to one of the cheaper restaurants, a hole-in-the-wall where you had to coordinate your comings and goings with the other patrons because the chairs were so close together. The best deal on offer was a salad for 119 kroner. This is roughly what I spent on a month's worth of meals in India.

Every college department in Denmark has a bar with cheap beer and frequent raucous parties. We managed to finagle our way into one Biology department's Friday night event. All the guests were dressed in Halloween costumes. It turned out I had little in common with these anachronistically-clothed biology undergrads, and I was moments from passing out on the couch, so I said my goodbyes and walked through the rain to the subway. I still had no cash and had to ride ticketless, banking on a dearth of ticket checkers or, failing that, the stupid tourist card. I was willing to bet that a Danish prison would be a sizeable step up in my standard of living.

Would you Care for Some Butter on that Oil?

The flight to Marrakech was equally snack free, but only lasted a few hours. I finished off the stack of stale peanut butter sandwiches I had assembled back in Gainesville. When arriving in this city a decade earlier, I had been struck by how unbelievably alien and underdeveloped it seemed; now it was as cushy and approachable as any Caribbean port town. Once I had convinced my bank that I was in fact in Africa, I took a grand taxi to Asni and another to Imlil. All the tourists here were gearing up to summit Jebel Toubkal, the highest mountain in North Africa. Every shop rented crampons and sleeping bags, though most were ill-prepared to tell you the first thing about hikes in the area. I followed a pair of Israeli guys to a guesthouse on the periphery where they negotiated the price of a room down to a mere 40 dirham. This was impressive, as the cheapest meal in town was 50. I could probably have saved a lot of money in the weeks to follow if I had only brought an Israeli along.

I had decided I didn't want to risk frostbite, altitude sickness, or sliding off a mountain, and I would do a low altitude valley hike rather than trying to bag Toubkal. From Imlil, a steep hike up a dry stream bed led to a pass which dropped down into an atmospheric multi-tiered village built into the mountainside. The trail tunneled back and forth, following tiny alleys between piles of homes; ladders and mud staircases led up to small doors recessed in each wall. Children scurried to and fro, peering out through open doors, playing hopscotch, and pushing around old bicycle wheels; some volunteered to be my guides through the multi-dimensional maze. Villages like this lined both sides of the canyon. Often invisible at first glance, the houses blended into the surrounding rock. My path led along the northern wall, weaving through one labyrinthine settlement after another.

I asked a small boy where I might find food, and, suddenly beaming, he took me straight to his house and led me to a rooftop table. His family came up and introduced themselves one by one, each attempting to strike up a conversation in Tashelhit, but falling back on pantomime. Eventually my food arrived; my lunch consisted of a round of bread, a bowl of oil, a plate piled high with butter slabs, and a teapot with mint and sugar. The Tashelhit word for leafy vegetables escaped me. I was suddenly thankful I had packed a pound of trail mix.

I arrived at Ouirgane where I expected to find transport back to the city, but there was only a soccer field, a mosque and a quiet dirt road to nowhere. I asked one man where I might find a guesthouse or the highway. He gave a nod of recognition, and gestured straight-ahead. I expected that he would just point me around the corner, but thirty minutes later we were still hiking through olive groves. We eventually arrived at a luxury motel on the main road. Naturally he wanted money, and he assumed I had a lot since I had asked for directions to this place that charged 1500 dirham a night. I discovered I had no small bills, and just as I was trying to sort this out, a taxi rolled up. I jumped aboard but the man put his arm through the door to prevent my escape. The driver revved the engine impatiently, and I dug out a small pile of American coins amounting to 55 cents and thrust them into his waiting hand; this caused him to draw back just long enough for us to make our escape.

Back in Marrakech, the Djemaa El-Fna was livelier than ever, overflowing with people who gathered around a hundred different street performers, and twice as many food vendors. Snake charmers summoned a dozen different species of serpent from all manner of receptacles, and chucked them around the necks of unsuspecting tourists, demanding payment when friends and family reflexively snapped photos. The bus station was closed for cleaning, but a random guy by the entrance was happy to sell me tickets to wherever I wanted to go. Since my destination was all the way down in the Western Sahara, he was happy to ask $40 for this ticket, which was really just a shred of paper with an arbitrary company name and some Arabic scribble. This was a large sum to hand over to a random guy at a bus station in the middle of the night, so I went around to the lot to find the actual bus and driver. The bus to which I was directed was going at least as far as Agadir. It could very well be continuing on to Tan Tan after that. How I would make it to Laayoune from there was a little more hazy, but the driver seemed confident that I would get there; "Direct Laayoune" he insisted, as he gestured toward the floor of the bus. I knew I was getting ripped off; I looked around for an Israeli, but found none close at hand. Dropping a stack of bills into the driver's outstretched palm, I grabbed my inscrutable ticket, and, plopping down, wrapped my jackets around my head and promptly passed out.

|

|

|

| Snow in Africa! |

|

| Not altogether reassuring |

Camel Pet Stop

We were deposited in Tan Tan at 7:30AM. My direct bus trip would resume on a different bus, three hours later. The city was rather bleak and there was no sign of its Star Wars namesake. At ten, my driver started up a decaying city bus in preparation for the five-hour journey south. When only a handful of people shuffled aboard, he turned it off and handed our fares over to a taxi driver.

Leaving the city, the first ten kilometers had beautiful bike lanes and street lights every few feet, but the second we passed the airport, this was replaced with a narrow, bumpy track through empty desert. After a few hours, our landrover pulled over next to a cluster of camels. The driver muttered something in Arabic and the passengers hopped out and wandered into the herd. One man chased a few across the road and out of the path of an oncoming truck. A woman in a burka shyly extended her hand to caress the sides of a few standing nearby.

A cop at a checkpoint just before Laayoune decided he needed to call everyone he knew to talk about the American trying to get to Mauritania. I sat in the cold wind for half an hour before my passport was returned, and then got back in the car with my head held low; the other passengers took it in stride.

|

| Camel pet stop |

The 4-Hour Overnight Bus Ride

Laayoune is a big, safe, pleasant city in the middle of the desert without a great deal going on. The night market is fairly massive and features creepy baby manikins hanging by their necks and creepy toddler manikins without heads.

The overnight bus brought me to Dhakla, which is marginally less pleasant and marginally more boring than Laayoune. It's on a peninsula, 26km from the main road, and this makes hitchhiking away difficult. Further diminishing your chances of getting a ride is the fact that several hours of driving separate you from the next settlement. If the driver finds out early on that you smell bad or are psychotic, he can't be like "oh, well I'm actually only going to this place a few miles down the road"; you would know right away that this is a lie, because that place he just referenced is empty desert. This inability to bluff prevents most drivers from stopping - even though every single one of them is going exactly to where you want to go. After waiting some time, I decided to go back to town and wait for the overnight bus. I found a man with a blender and taught him how to make a banana milkshake. I hope these catch on.

Since I had yet to stay in a place with a shower, I decided to hunt down a public bath as a consideration to my fellow passengers. I stopped at half a dozen hotels to ask for directions but each clerk tried to sell me on paying $10 to rent a room for an hour. After several hours of wandering down random alleys, I spotted a sign in Arabic with opening hours and a price of 10 dirham. I asked the attendant at the entrance and he confirmed my hopes that it was indeed a hamaam. Arriving in the changing area, I realized I had little notion of proper procedure, and I certainly didn't want to leave all my possessions in a cubby two rooms over. I awkwardly entered the steam room fully clothed and found a large man in swim trunks vigorously scrubbing another man lying in the middle of the floor. There were no hooks in this room, so I went to the next one, hung up my bag and clothes and dumped water on myself. I was able to retain enough of the warmth of the steam when I left that I was hardly bothered by the interplay of the frigid desert winds with my sodden undies and dripping hair.

And that brings up an important point - when the Harmattan is rolling through, West Africa is cold at night. Morocco is even cold during the day. I had strongly considered ditching my jackets the second I entered this southerly continent. I would have regretted this.

There were two buses lined up next to the station and neither had an intelligible sign. One of them had a crowd of black people waiting next to it. I had not seen black people until this point, so I concluded that this was the bus that would take me south.

When I had bought the ticket, the man at the desk had assured me that the bus would arrive at the border at 6am. When compared to the other distances on the map, the stretch didn't look like it should take 10 hours, but I supposed we would be plowing through dunes or crossing some other formidable obstacle. The road turned out to be quite fast. We arrived at 1am.

We pulled up to a hotel and, after several minutes of confused shuffling, the proprietor informed me that there was no space left. I asked the driver if I could sleep on the bus where he was readying to spend the night, but was told it was impossible. I prepared to curl up on the bare stone porch with the black people; all the olive-skinned passengers had found a place inside. I noticed one of the hotel's employees and another man were wandering into the desert, and I ran after them. It turned out that the employee's room had been rented out and they were going back to the insurance office where the other man worked to sleep; I went with them and was given a bed, blanket and pillow, and thus made it through the night without unfolding my space blanket.

The following morning, everyone was gathered in the hotel lobby to eat crepes and cafe du lait, and await the opening of the border. The TV was playing an Abu Dhabi broadcast of a National Geographic special about axolotls, a rare species of Mexican salamander with regenerative limbs. My friends and I had once started a nonprofit whose mascot was an axolotl. Small world.

When they finally let us through the gate, we all lined up our passports on a counter next to a window, which was open just wide enough to admit one passport, and then went up one-by-one to peer through and talk to the official. After waiting half an hour, I was informed that, since I did not yet have a visa for Mauritania, I needed to talk to another set of police across the way. After getting their blessing, I was sent back to the original line and waited again for the official there to give me the requisite stamp. My documents were thoroughly examined four more times before I finally made it out of Morocco.

"You should get a taxi - there are men out there who hunt people like you," a man explained as he gestured out into the 4km stretch of empty desert that separated the two countries. Never has there been a "No Man's Land" more deserving of the moniker than the landmine-riddled wasteland between Morocco and Mauritania. Burned out cars and broken TVs lined the rough 4wd sand track. I walked a little ways out and extended my thumb. A compact, already carrying 7 people, stopped to squeeze me into the seat straddling the stick. The driver wanted 50 dirham for the ride. Luckily I only had 14 left.

On the Mauritanian side, I had to obtain a visa, which could only be paid for in euros. It might have been reasonable to assume that you could pay for such a visa in ouguiyas, the national currency, but euros were the only way. I went to the one exchange counter in the ramshackle desert outpost and haggled them down to the somewhat exorbitant price of $75 for 50 euros. With the visa in hand, it only took another hour and a half to get through the remaining officials.

Dunes, Dust and Diesel Fumes

I chose this title purely for its alliteration - there are no dunes in western Mauritania. There isn't much of anything. I had paid 5000 ouguiyas for the 5-hour ride to the capital of Nouakchott, which passed through the occasional settlement of scattered shacks, in the midst of hundreds of miles of shapeless void. How these people got food or water, or what they did for work, or why they chose to live half a kilometer from their neighbors, staking a claim to acres of grey, featureless sand - these answers eluded me. It was a little bit like Texas, but with no cars with which to go anywhere else, and considerably fewer fast food outlets and big-box stores.

Nouakchott is a city of sand and exhaust. The streets are bordered with deep drifts, and the air is choked with dust and fumes. Walking is not an option - taxis and private cars - preferably acclimatized ones with tightly sealed windows - are the only way to survive. When our shared taxi dropped us off, I set off to find a guesthouse advertised in the guidebook. After trying in vain to read the tiny writing on my Kindle's city map, I started going from store to store, and eventually found a pharmacist who spoke excellent English and paid two taxi fares so he could accompany me straight to the gate of the hotel.

I paid 2000 for a bed in a tent on the roof. My mosquito net was full of mosquitoes. The bathroom was full of mosquitoes. The community bookshelf was, quite bizarrely, full of mosquitoes. There was a robotic Che Guevara sitting in one of the lawn chairs that regularly nodded his head and tapped his foot, and I was pretty sure that his beard was full of mosquitoes. The next day I learned that this was not a robot, but another hotel guest, though I never once saw him leave that chair. Vendors on every street corner were selling Chinese pop-up mosquito tents. It seemed likely that there was an epidemic of some kind.

The next day I went to the Senegalese embassy on the other side of town to get a visa, only to find out that I needed to pre-order the visa online (I'm pretty sure they use TicketMaster) and bring in a printout. The only internet cafe was next to my hotel, so I had to return there to pay the 50 euros, and $4 convenience fee, and get the printout, and then I returned to the embassy. They told me to come back in two hours, so I went looking for the Guinean embassy. I never figured out if this actually existed; some seemed to think it did. One taxi driver agreed to take me, drove in circles around town for half an hour, decided it didn't actually exist after all, and asked for three times the normal fare.

I had to pay 1000 to get to the southern bus station and another 3500 to reach the border at Rosso four hours away. I had read that the border closed at 6, but it still seemed to be going strong at 6:30. I had also read that this particular post was horrendously corrupt, expensive and frustrating; this proved to be pretty much spot-on.

|

| No man's land |

|

| More or less all there is to Mauritania |

Escape from Mauritania

Upon exiting the packed minivan, I was immediately approached by a man in a long, blue cloak. He held up an ID card and explained that he was a guide. I explained that I was perfectly adept at crossing borders on my own and didn't need a guide. He countered that I didn't know French and had no way of navigating the border formalities. I responded by frantically waving my arms up and down and yelling at him in a vicious string of nonsense syllables. He followed me to the border gates.

In the first room, there was an official responsible for entering my passport info into a computer. He was remarkably bad at it. He had to reenter my name six times. The guide told me that I needed to pay him 2000 ouguiyas. I said that yes, this was certainly true. Then I did nothing. The guide eventually grew impatient and yanked my passport away from the man so we could advance to the next station. I don't know if my passport info ever got entered into that particular computer.

The guide told me to buy ferry tickets for the two of us. When I questioned why I should be buying one for him, he bought them himself. These were 100 each, and a pittance compared to what he planned on making off me.

We went on to a pair of officers in charge of stamping passports. The guide explained that I would need to pay 5000 for this service. He then went around to the side window to negotiate his cut. One of the officers stamped my passport and said in English "Free, you pay nothing for this".

We boarded the ferry and I took off into the crowd, trying to put some distance between me and the guide. Prompted by this action or my guide's behest, a man dressed in a military jumpsuit approached me and asked for my passport. He had no labels or identification displayed, so it was unwise and unnecessary to hand it to him, but I did and he immediately turned and rushed off the ferry, and I had no choice but to follow him; the ferry began pulling away just as I took the final step back into Mauritania. This was the evening's last scheduled departure.

I was pulled into a dark room at one end of the compound, along with a Senegalese man who had been yanked off the ferry in the same way. The interrogators wore plain jumpsuits - there was nothing to suggest they had any authority, aside from their access to the dank cell where they held us. I concluded it was all some sort of ruse, and ran outside to the nearest person in uniform; he accompanied me back into the room. They told me to open my bag and, at the same time, emptied the contents of the other man's satchel onto the desk. Suddenly a pile containing tens of thousands of dollars in euros and other currencies lay before them. They seemed less interested in whatever my stinky daypack might contain. I told them I was going to leave, and without even looking over, they nodded and waved me out.

My guide spotted me as I re-entered the courtyard and started to head over. I noticed a pirogue at the dock, at the moment unlashing its ropes from the cleats, and I sprinted to reach it. The boat was full to the brim with passengers and vegetables; I thrust my 300 ouguiya fare at the assistant and tumbled into the fray. The boat pushed off before the guide could reach us. His hour of chasing me around had netted him a loss of 200 ouguiyas.

As West as West Africa Gets

On the Senegalese side, a man in plain dress acted as my guide and escorted me through the crowds to get my passport stamped. He led me to a random shack to exchange for CFAs and probably took a pretty hefty commission from the 15% spread between what I got and the bank rate. Next he took me to a bar, and seemed surprised when I suggested that, since it was already around 8PM, I might want to try to find a bus onward, rather than spend the last few hours of the day drinking at the border. He grabbed a taxi for me to the bus station and insisted that the half-mile ride cost 3000CFA; I haggled this down to 1000 and stormed off when he asked for his fare back to town. Compared to Rosso, this side was cake.

I found a bus to Dakar and initially paid to be let off halfway at St. Louis. I later decided that there was no use in reaching the seaside town in the middle of the night, so paid the rest of the fare to the capital. Over the course of the ride, I befriended one of the passengers who offered to let me stay at his house. We got off just short of the city around 5am and caught a taxi to his place in the suburbs. He directed me to a bed that already had two men sleeping in it.

The next morning we took a bus to the neighborhood of the Guinean embassy. Charif met several friends who were driving to the festival of Touba, and explained that we would be tagging along. Touba is an annual Islamic festival where most of the population of Senegal goes out and prays and parties in the desert. Pretty much everyone in town was going to Touba. I got a visa to Guinea for $130, then we spent the rest of the day trying to find tourist attractions in Dakar.

Charif's friend's car never showed up; this may have had something to do with the fact that the engine was largely held together with masking tape. At 9PM, we went to a nearby traffic circle to wait for a bus. Occasionally someone would yell "Touba" and a hundred people would mob the bus, vying for one of the few remaining spots. All manner of vehicle, many of which would never be deemed worthy of interstate travel any other day of the year, had been repurposed to make the 200km drive. Young men clung desperately to the sides of trucks, their enthusiasm girding them against the chill of the night air. It seemed we had little chance of securing a spot, since Charif had several massive packages he was carting around, and a vehicle would never stop for more than a few seconds, for fear of being completely overrun. But just when I was fixing to go to the bus station to find a ride somewhere else, an empty city bus rolled up and my host wrestled past the other prospective passengers to reserve two seats.

The window next to our seats was missing; at first I regarded this as a boon for all the fresh air it afforded us, but once we got up to speed, it quickly became apparent that the rushing 45 degree air could might very well kill us. We erected a curtain from three different jackets that held out the worst of the breeze and suffered through a frigid, sleepless 6-hour ride. We got off to grab a taxi around 5:30AM; I didn't realize it at the time, but Charif's family home was 50km short of the festival grounds.

Like a Really Huge Islamic Burning Man

We spent the morning visiting all of Charif's family and friends; everyone who had ever lived in his village had come back from wherever they now lived, some from as far as Ghana and America. One friend gave me a free t-shirt pr€oclaiming the greatness of Amadou Bamba. Around noon, we attempted to find onward transport to the festival; it would've been very wise to have remained on the bus that morning.

I would hear on the radio later that day that there was expected to be three million people in attendance this year. When you think of the logistical challenges of organizing an event of any significant scale in America, you wonder how a country like Senegal, with substantially less transport infrastructure, communication, and functional government, could ever possibly pull something like this off. How could they funnel that many people down a single two-lane road into a city built for half a million?

We took a donkey cart to the bus station; we should have taken this donkey straight through the desert to the festival. It took the better part of an hour to find two spots in one of a rapidly dwindling supply of functional vehicles. We spent the next three hours sitting in traffic, averaging slightly slower than a relaxed walking pace. Even this far out, the streets were full of revelers, and many passed free bags of water and food through the windows of the bus. At this rate, it would be days before we reached the festival. Buses on the other side of the road zipped along, making good time back to Dakar where they would fill up again and make the return journey. In the gaps between return traffic, our bus and others would jump to the other side of the road and make as much progress as they could before having to weave back into the line. Many simply drove through the empty sands surrounding the highway. Eventually I decided I had no desire to spend the next several days sucking in diesel fumes and jumped out the window, apologizing profusely to my generous host, and then jumped on a bus heading in the opposite direction.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

An Old-Fashioned Family Roadtrip

I arrived at the junction with the main road and joined a string of people hitching with eastbound traffic. Few cars stopped and the onset of night found we wishing I had just kept going to the Dakar bus station. Finally, a bus slowed with men hanging out the door shouting 'Tamba, Tamba' and I hopped on. They had put serious effort into making this bus uncomfortable; the seats actually all tilted forward and leg room was negligible - my particular seat was over a wheel well. Whenever we took a turn, the tire under my feet would rub against the well and unleash a plume of acrid black smoke into the cabin. I wanted to get off, but it was night and the odds of getting another ride were slim, so I sat quietly and waited for a catastrophic blowout. At one stop, I asked to sit up front and they found me a fold-up seat, which was, at least, a little bit further from the source of the smoke. There was no seatback, so my every attempt to sleep (about once every thirty seconds) involved resting my head against the guy in the seat next to me; he wasn't very cooperative in this regard and would swat me away each time, only to have me plop my head back down half a minute later. We arrived in Tambacounda an hour before dawn and I wandered over and found a relatively clean patch of ground under a market table where I could nap.

I received two contradicting sets of directions to find a bus to Guinea, but the easier set led me to a station just around the corner. I said the name of a city just across the border and the station manager corrected me with a name that sounded similar, but, at the same time, completely different; I bought a ticket to that place, assuming that I had provided enough supporting details to eliminate any doubt that I was going to the right place. We quickly assembled seven people and took off in an old Peugeot for wherever it was we were going. The car was not in the best of shape, and the driver spent an hour cobbling together a fix to get the thing to run. We made it 10km out of town before it became apparent to him that the transmission was just about done and we wouldn't make it to our destination. He turned the car around and puttered along for another 5km before it broke down for good. We sat on the side of the road for half an hour, hoping another driver would be sent from the station, but none came; somehow the car was push-started, and we cruised at 10mph the rest of the way. It would only seem logical that, with a full car ready to go to an expensive destination, a new driver could be found immediately, but none were available for three hours. A car going to the same place, that had only one passenger and a goat when we arrived, ended up leaving two hours before us.

As the group finally began its journey in a new car, I tried to confirm with my driver that we were going the right way, but some 50km out of town, I finally ascertained that we were not going to Guinea, and I got out in the middle of nowhere, forfeiting my expensive fare. I hitched a ride on a motorcycle back towards the junction where I could find the ride I needed, but it ran out of gas a few kilometers later. I walked with this man for another half hour as he rolled his bike into town.

At Medina Gonasse, I found the cars going directly to Labe; these were 7-seater Peugeots, decked out in American flags and Obama stickers. The ticket was a hefty $30. Myself and a group of Guineans that seemed to number far greater than 6 bought our tickets and loaded our stuff onto the car. When everything was ready, we push-started the car, and it drove off without us around the corner. We wouldn't see it again for three hours. It was unclear whether the others understood what was going on during this time - I hadn't the foggiest. Eventually we walked around the corner and down the street and loaded into the station wagon. In total, we were 5 men, 9 women, and 8 babies.

We crossed the border with little trouble; everyone else paid off the officials on both sides, but they showed little interest in extracting any extra fees from me. Around sundown, we stopped in the town of Koundara for dinner. Everyone shared a huge plate of rice and groundnut soup, identical to the staple of Sierra Leone but bearing the French name 'sauce à l'arachide'. Just before leaving, I went to a public latrine - since I only had CFA, the driver gave me 1000 francs to pay the fee - and this is where disaster struck; as I finished emptying a bucket of water into the hole, I accidentally dropped my hoodie on the mouth of the pit. This hoodie was my pillow and a critical source of warmth, and now I had dropped it in a third world toilet. I had no idea when I would be able to wash this again; I certainly hadn't found any opportunity for laundry up until that point. I wrapped the 'clean' parts of the hoodie around the wet parts and stuffed it back in my bag, maintaining the foolish hope that it wouldn't contaminate the rest of my clothes with its absorbed poo water.

The wonderfully smooth asphalt ended and the next eight hours were spent on a rough 4wd track through the jungle. Our driver expertly navigated the heavily rutted road at a fairly obscene speed, and effortlessly circumvented every obstacle in our path. At one point we got out to load onto a cable ferry, and two men spun a crank to power us across the stream. Vendors, who had set up next to the ferry in anticipation of our 2am arrival, sold us yucca and oranges as we waited for our car to be unloaded. As on the previous night, there was nowhere to rest my head and, as a result, I fell onto the woman next to me every few minutes, and, as on the previous night, she would immediately swat me away every time; it seems West Africans are not great team players when it comes to sleeping on public transport.

We arrived at a taxi stand/hotel around 4am. The driver told me I could sleep in the car. Everyone woke up at 7am, and I readied myself for the next leg. After sitting in this manner for some time, the driver informed me that we had in fact already reached our destination of Labe.

A Trail of Breadcrumbs and Oranges

Wandering around Labe, I eventually stumbled upon the district Peace Corps hostel and, without having to flash my invalidated ID, was given a pass to go in and chat with whichever volunteers might be staying there. The one volunteer on-hand gave me the names and numbers of several others stationed in neighboring villages and highlighted those who were looking into ecotourism specifically. Equipped with these, I started walking south through the farmlands to search for trails connecting the district capital to the junction town of Pita, and onward to the ecotourism hub of Dalaba.

I asked for directions in the first village I reached and quickly discovered that no one in the village spoke a word of French; this would turn into a common theme. Unlike in Sierra Leone, where you can get by with Krio nearly everywhere, it is difficult to find anyone in the Guinean countryside that speaks anything other than the local language (Pular in this region). Since the only word that could be conveyed was the name of the town to which I was heading, several children were dispatched to take me ten minutes out off of my path to the main road leading to Pita. The area was densely populated and every village had a pump where I could hand my water bottle to the nearest child and it would quickly be returned to me full to the brim. The locals did not understand the bizarre lifestraw contraption I insisted on using to drink all my water.

At one point, I reached an intersection and approached a man in the hopes of figuring out which trail to take. He quickly did a 180 and speed-walked in the opposite direction, nervously looking over his shoulder as he went. I gave up my pursuit and headed the way I had been going before. Looking over my shoulder, I saw that he had turned and was following his original path. This man was likely insane. You meet a lot of insane people in the developing world. They don't have anywhere to put them.

I asked one lady crossing my path for directions and she took me back to her house, made me a pot of tea, and had her children pick 30 oranges for me. I had to politely decline 25 of these on the grounds that I had no space to store them - I had already attached my breakfast sandwich to the outside of my 18L pack with a carabiner. Since she only spoke Pular, she had no way of giving me directions, so she took me back to the path I had arrived on, smiled, and waved farewell.

A man on a moto stopped to see if I wanted a ride. It was getting late so I hopped on; he drove me to the next town and dropped me at the taxi stand, and waved off my efforts to pay him. I hopped aboard a vegetable truck that would take me the remaining 10km into Pita. It was full of market vendors, very much bemused by my presence. One baby stared at me the entire time, with eyes that were the very image of awestruck wonder.

In Pita, I bought a Guinean simcard and called up Chris, the local volunteer. He and five others who were visiting met me a few minutes later at a local sandwich shop. We ate corned beef sandwiches and painfully sweet cafe au laits, then went to a nearby hotel for beers. We went back to Chris's place where he set up a space for all of us on his living room floor. I was up at six the next morning to hike onward to Dalaba. He and the others were leaving first thing to head over to Doucki, the great eco-tourism success story of the country; I had fished for an invitation, but it seemed they were looking to celebrate Christmas amidst close friends.

Any search for hiking in West Africa is likely to point you towards Doucki, and the energetic guide Hassan. This man had pieced together a collection of local paths that wound through caves and up vine ladders, and, using his mastery of French, English, and several other languages, had guided scores of international tourists through his jungly paradise. Peace Corps volunteers had discovered him and helped him to develop an effective business plan, and he now charges $25/day which includes meals cooked by his wife, a stay in huts he built to house tourists, and one of a dozen different day-long hikes.

As I followed the main street to the outskirts of Pita, I searched diligently for food, but found that every restaurant was shuttered. The only option that came along was a pile of meter-long baguettes; I bought one of these, thinking it was all I would encounter that morning. Starving, I ate two-thirds of the bread, and instantly regretted it - there is a most terrible sensation of being sickeningly full, but simultaneously, completely malnourished, that can only come from eating a pound and a half of white bread, or an entire box of poptarts. I eventually found a woman with a beans and oil sandwich stand, and got her to spread the mix on what remained of the baguette.

I tried piecing together footpaths to fashion a route to Dalaba, forty kilometers to the south, but as on the previous day, finding any sort of coherent sequence using only my gps and local knowledge, proved nigh impossible. At one village, two men proposed two alternative routes; I understood neither choice, but explained half a dozen times that I wanted to follow small footpaths and not use the major roads. One of the men said that he understood, and promptly gave me a free ride on his motorbike to the main highway.

I started to follow a path leading away from the highway into the countryside. Immediately a man holding a machete with a wild look in his eyes waddled up to me and said "I lek you". He said this six more times as he drew closer. I decided this was not the route I wanted to take and returned to the highway. From there, it was an easy matter to hitch a ride the rest of the way to Dalaba.

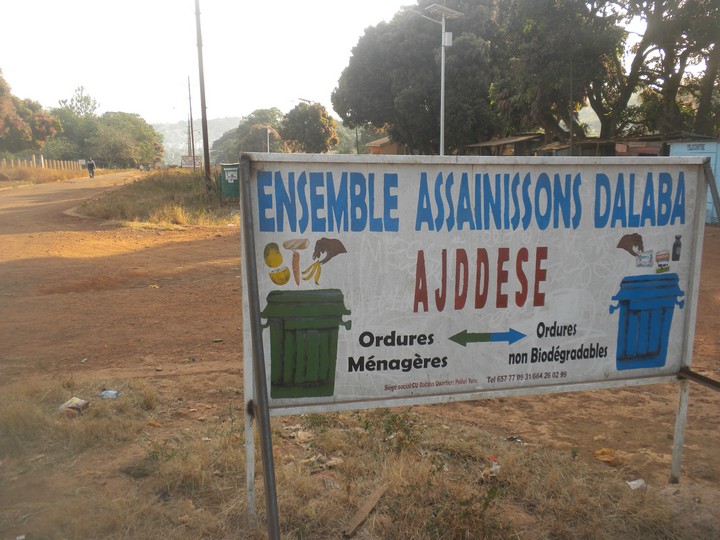

Christmas and Toilet Paper? Better Ask at the Mission

|

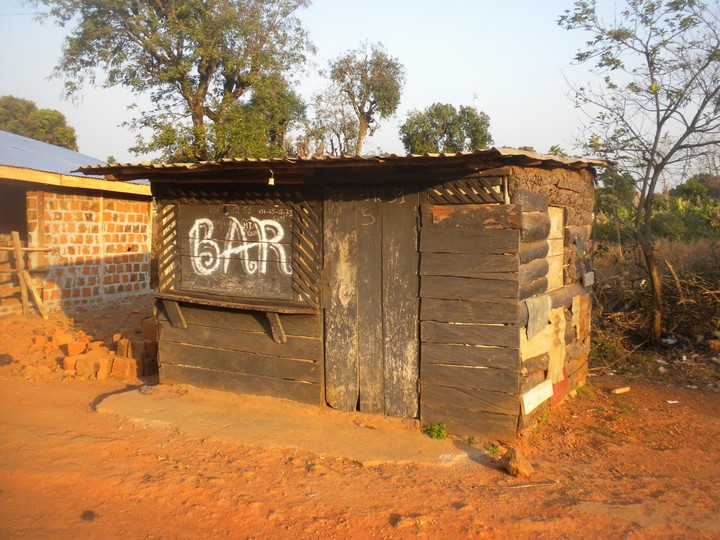

| The local eco-tourism office |

|

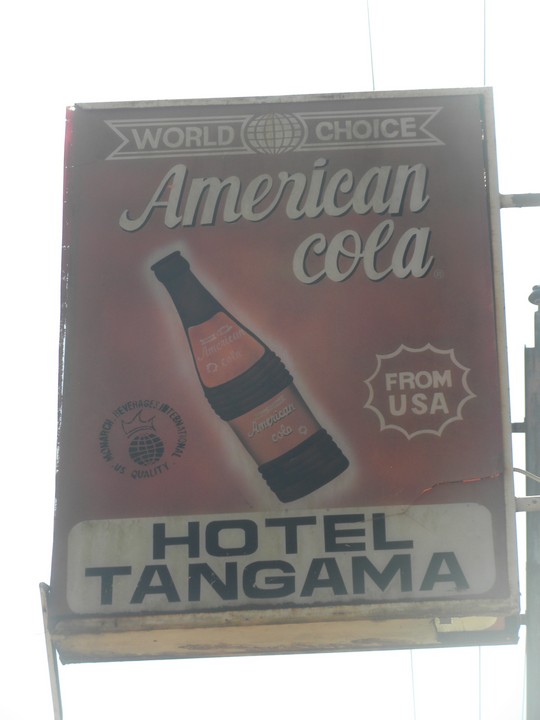

| I have never heard of this cola |

|

| Innovative gate |

|

| This boy's backpack is made of a printer box |

|

| One PC volunteer's primary project |

|

| Half-finished mansion |

|

| Ice cream store in a shipping container |

|

| One of the world's sketchier bridges, made from ribbons of dismembered steel cable |

The Fiery Streets of Hell

|

| Not the first place I would've chosen to hang out for 16 hours |

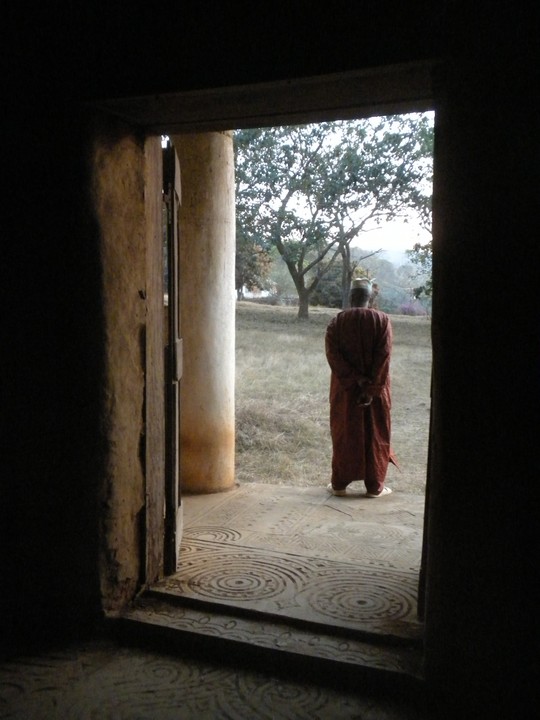

Monsieur Doucement

|

| Monkeys in the mist |

|

| One of 17 repairs made over the course of our journey |

|

| Wonderfully sexist ad for seasoning |

|

| On our 4-day, 200-mile journey, we got passed by dump trucks, bicycles, and this guy |

|

| Our driver is all tuckered out after a long two hours |

Next Stop: Warsaw

Trapped in Paradise

|

| Praia's praia |

|

| One of a few billion giant spiders on the island of Santiago |

|

| View from my luxurious villa |

|

| The run-down but unusually well-signed Serra Malagueta Park |

|

| The half-finished McMansions of suburbian Tarrafal |

|

| Cow-driven cane mill |

|

| Paying $25/night is no fun, but you get your money's worth |

|

| Deluxe included breakfast |

|

| Ciudad Velha's ruined cathedral |

|

| Bar/restaurant on a bus! |

|

| The eerie Pedra do Luma |

|

| Espargos' one sight |

Two Salads Only

|

| Africa's rice porridge and oil sandwiches have nothing on the English breakfast |

|

| The library |

|

| The Museum of Science and Industry's sewer exhibit |

|

| Manchester may have presented the largest language barrier of the trip |

|

| The Exchange Theater: Classical-style architecture meets the lunar lander |

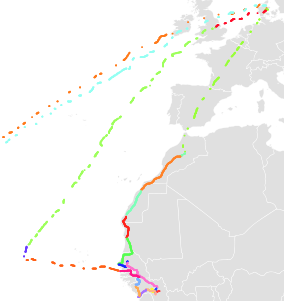

Costs

Norwegian flight from Fort Lauderdale to Copenhagen: $184

Norwegian flight from Copenhagen to Marrakech: $94 (on the expensive side - you should be able to find these for $50 or less)

Bintas Canarias flight from Banjul to Praia, Cape Verde: $200

TACV flight from Praia to Sal, Cape Verde: $112

Thomson flight from Sal to Manchester, England: $300

EasyJet flight from Manchester to Copenhagen: $86

Norwegian flight from Copenhagen to Fort Lauderdale: $300

Visa for Senegal: $70

Visa for Mauritania: $75

Visa for Guinea: $135

Visa for Gambia: $25

Visa for Cape Verde: $40

Cheap meal in Copenhagen: $22.50

Cheap meal in Morocco: $2.50

Cheap guesthouse in the Atlases: $5

24-hour bus from Marrakech to Dhakla in the Western Sahara: $50

Cheap meal in Mauritania: $1.50

Shared taxi across Mauritania (8 hours): $30

Rooftop bed in Nouakchott: $7

Bus from border to Dakar: $10

Dakar city bus: 40 cents

Senegalese Rice dish or omelette and coffee: 80 cents

14-hour taxi from Tambaconda to Labe (in Guinea): $30

Rice and plasas in Guinea: 70 cents

Local Guinean beer in bar: $1

Hotel room with bathroom in Guinea: $10

Bus Dalaba -> Mamou: $3

Coartem Malaria treatment course: $2

Big cup of ice cream: 60 cents

Rice and plasas in Gambia: 65 cents

Cheapest hotel in Cape Verde (but good value with breakfast): $25

Bus Praia -> Assomada: $3

Street food in Santiago: $2

Cheap restaurant dinner in Santiago: $3

Rice and 3 curries at Indian restaurant in Manchester: $6

All-day bus pass: $4

Loaf of wheat bread: 70 cents

Total: $2287 (so much for finding a cheap way into Salone and living off the good will of villagers)